By: Mayan Sarnat – a research colleague of the Alma Center

Iran needed manpower that, on the one hand, is skilled and professional, but on the other hand, is trustworthy and politically and religiously faithful. It turned out that those who are qualified for the job professionally are not among the regime’s supporters. Iran’s need to balance between ideology and cyber-skill brought it to establish its cyber warfare array using contractors as its proxies.

Iran’s preferred method of fighting its enemies, ever since 1979, was the use of proxies.

In 2009, Iran began developing cybernetic capabilities that would allow it to harm its enemies whilst preserving ambiguity. The rise in civil riots at home and the escalation of its struggle with Israel and the United States (an increase in sanctions and attacks by Israel on Iranian interests in Syria since 2013), made clear the regime’s top priorities – the need for swift acts of retaliation, as well as keeping an eye on its home opponents.

Cybernetic warfare, that allows Iran to keep a low intensity conflict, deny its involvement, and wreak havoc with relatively little effort, became its preferred method of operation. Iran began developing offensive capabilities for the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ intelligence unit, but at the same time was forced to contend with a severe internal structural challenge.

Iran needed manpower that, on the one hand, is skilled and professional, but on the other hand, is trustworthy and politically and religiously faithful. It turned out that those who are qualified for the job professionally are not among the regime’s supporters. Keeping the balance between ideology and cybernetic skill remained problematic for the regime. A prominent example for the gap between ideology and skill is Mohammad Hussein Tajik, former commander of the Iranian Cyber Army. His father lived a religious life and even worked for Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence. Despite his loyal background, Tajik was arrested and murdered because the regime suspected he was not sufficiently ideologically aligned and prone to treason.

Iran wanted to rapidly upgrade its cybernetic capabilities, but the manpower recruited for this task turned out to be young, relatively liberal, and focused on financial gain. This generated inherent distrust between the regime’s representatives and the skilled manpower, with the regime believing this manpower would be taken advantage of by foreign intelligence services as intelligence sources.

To mitigate this challenge the regime adopted a distinct approach. Iran employs a network of people unofficially affiliated with the regime, an ideologically loyal mid-management of sorts, that translates intelligence priorities into cyber missions that then are given to contractors.

Sometimes, the contractors are instructed to compete with each another and sometimes to work together. Only after the job is done do they get paid. The result is a motivated, self-learning and self-improving competitive system, that pits contractors against each other in a struggle for the regime’s purse. There are over 50 organizations assessed to be competing for cyber projects in the Iranian offensive cyber field. Thus, in effect, the contractors become proxy for Iran with a specialization in types of attacks and targets.

The tools and tactics used in cyber warfare are in danger of being exposed. Unlike conventional weapons, cyber-attacks are less effective when they and their functionality and infrastructures are revealed. A technical description of missiles does not provide effective protection against them, but a description of malware can provide antivirus companies and administrators with the ability to protect against them.

Contractors operating on behalf of their countries will normally not use the most sophisticated tools and technologies available unless their target’s importance justifies tipping their hand. In Iran’s case, cyber-attacks are generally simple, focusing on “easy” targets, such as private companies. And yet, the contractors’ decentralized nature makes it difficult to identify and locate them.

Malicious malwares publicly attributed to Tehran are usually “abandoned” immediately after being exposed, never to be used again. It appears that the various cyber warfare groups disband and split up, employees transfer between them, forming inter-group alliances and cooperation that blur the lines between them.

Contractors/Proxies

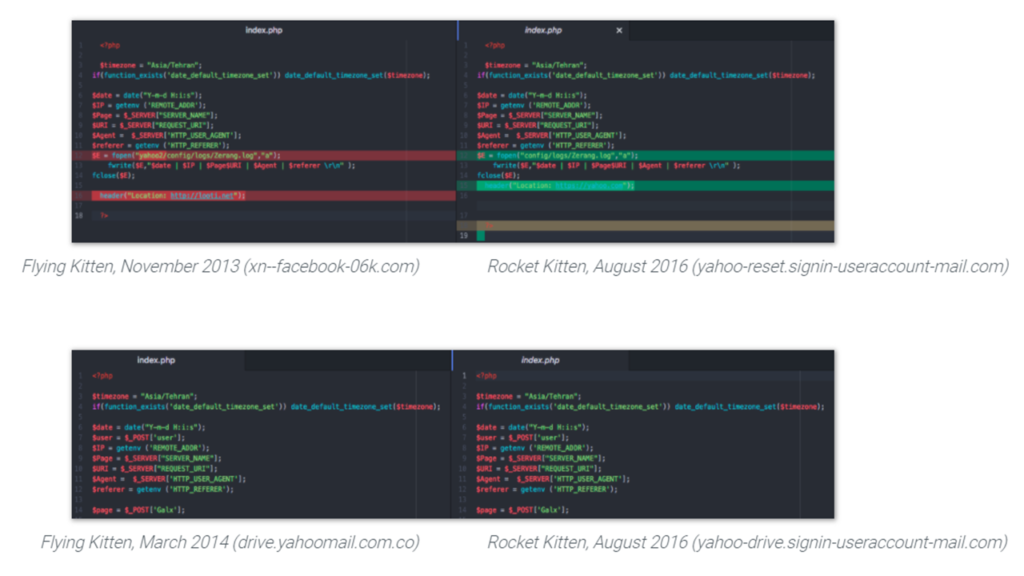

There are two supposedly distinct groups: Charming Kitten, a.k.a. Flying Kitten, and Rocket Kitten. Due to the overlap in the infrastructures, tools, objectives and methods of operation of these two groups, researchers find it difficult to accurately attribute any event to this or that player. While Iranian cyber groups are well documented and researched, their connectivity and general eco-system are not well understood.

Charming Kitten was one of the first groups to be described as a coherent threat actor operating against the regime’s political opponents, and foreign targets.

In a phishing campaign it waged in 2014, emails and private social media messages were sent to members of the United States’ defense sector. The attackers created the domain/website named “aeroconf2014 [.] org”, masquerading as the IEEE Aerospace Conference (the real address being aeroconf.org), and sent the following information:

From: invite @ aeroconf2014 [.] org

Subject: IEEE 2014 Aerospace Conference

The email encouraged its recipients to visit a fraudulent conference website owned by the attackers. Upon visiting the website, they were required to download a 3rd party software in order to access the website’s relevant information, which in fact was a malicious malware that stole information from their computers.

A few months after the collapse of Charming Kitten’s infrastructures following their unveiling in late 2014, Rocket Kitten entered the picture and began appearing in various research reports. While the two groups showed different behaviors, thus supporting the assumption that they are two different groups, their shared use of unique tools indicated that Rocket Kitten used Charming Kitten’s code for stealing user credentials from its victims. Even more so, Rocket Kitten made use of a malware that was found to be a kind of earlier development of the malware used by Charming Kitten. These congruencies indicate that Rocket Kitten had some form of contact with Charming Kitten. The members of the latter possibly even joining the former.

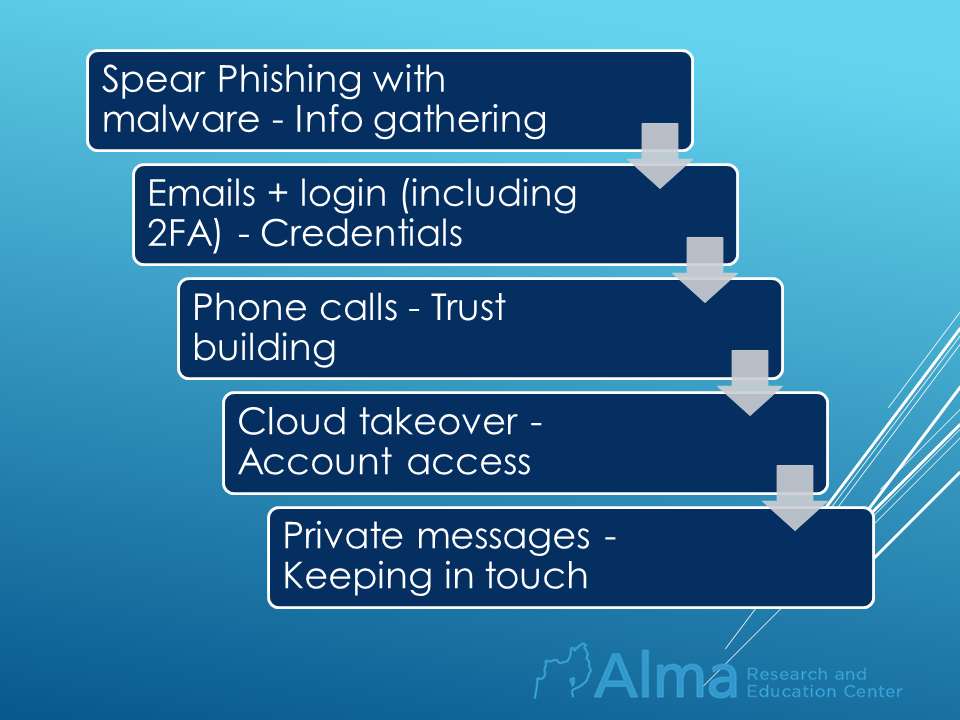

In 2015, Rocket Kitten waged a series of attacks on security company employees, academia members, and researchers in Israel and the Middle East. For example, the group launched a two-week-long attack on a single target – a researcher at the University of Haifa: (1) Phishing emails were sent, impersonating a victim’s acquaintance and including malware that collected information from the computer. (2) Three separate emails were sent with links to a fake login page (that “stole” the victim’s username and password, requesting a two-factor authentication to access the following page in order to establish trust with the victim. The hacker then sent an SMS message to the victim using its number that was obtained from the previous infiltration to the victim’s email). (3) Two telephone conversations with the victim were made by the hacker in order to further build trust with the victim. (4) Several attempts were made at taking control of the victim’s cloud accounts by using their recovery systems. (5) Many messages were sent to the victim’s Facebook page and email.

The attack’s trigger – the researcher from the University of Haifa became a target for the cyber-attack as a result of a radio interview she held on the topic she specializes in – Iran. –

14% of the group’s attacks over the years targeted Israel, while 44% targeted Saudi Arabia. Since 2016, Rocket Kitten’s status has been undermined, and today, its presence is felt only as “echoes” of other groups’ campaigns.

Oilrig / APT34

APT34 primarily performs long-term cyber espionage operations, focusing on surveilling industries for Iran. It has been active at least since 2014 and incorporates different methods of attack, primarily phishing campaigns against compromised accounts, using social engineering tactics.

The group carried out targeted attacks on systems in the finance, government, energy, chemistry, and telecommunication sectors. These attacks mostly targeted industries in the Middle East. All in all, (as of April 2019) analysts of the group identify almost 13,000 accounts whose details were stolen, over 100 malicious codes sent to victims, and dozens of hacks into systems in 27 countries, 97 organizations, and 18 industries.

In January 2020, APT34 launched a campaign in which it sent malicious email files to clients and members of Westat, a company closely associated with governmental agencies in the US. The company provides research services to local governments, as well as to more than 80 federal agencies. In the attack, a malicious file was sent via email (named survey.xls), that masqueraded as a survey for customers and employees. The emails contained Excel files that seemed empty at first to the victims. Only after they downloaded the files, they saw the actual survey, while a malicious program ran simultaneously on their computers, allowing it to extract information from the system, download files and perform various actions.

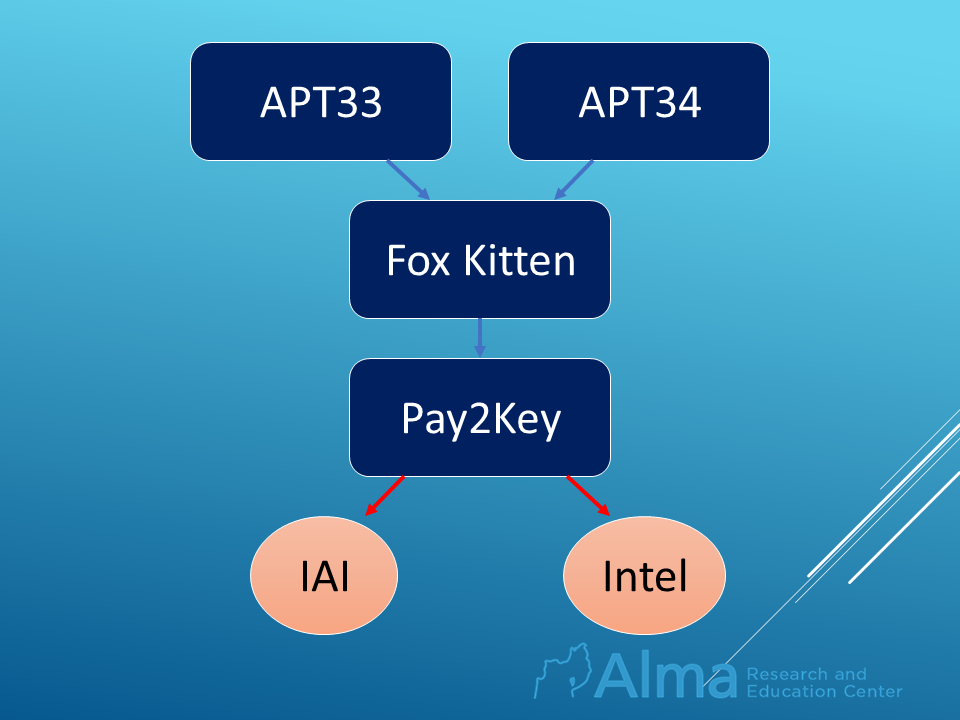

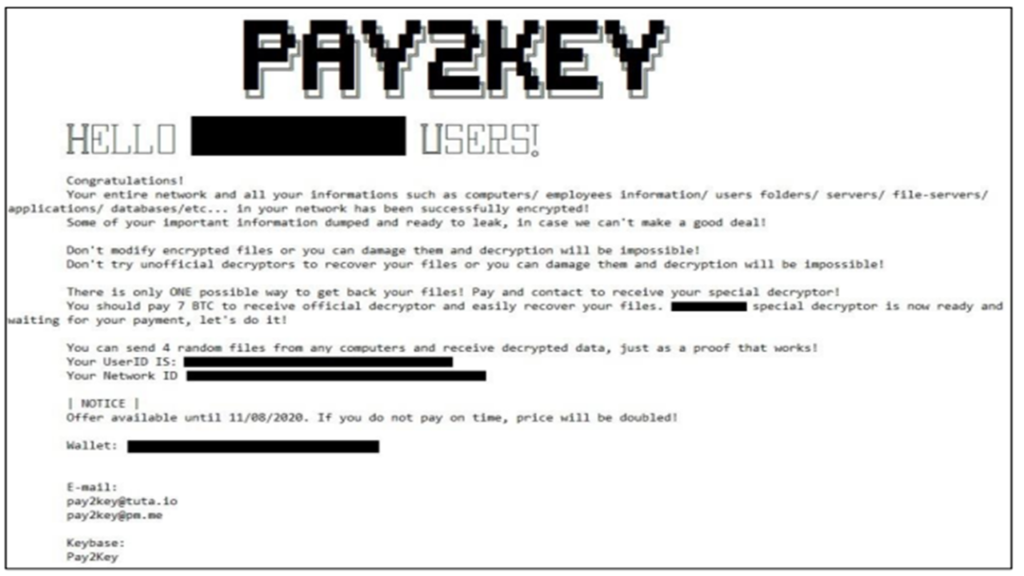

The group’s name was recently mentioned with regards to an attack carried out on industries in Israel in December 2020. The attack was attributed to the Iranian threat actor Pay2Key and was carried out on the offices of “Intel” Israel and of the Israel Aerospace Industries. Details of sensitive accounts were leaked and their content exposed to the attackers. The group Pay2Key was revealed as a product of the Iranian group – Fox Kitten, which specializes in attacking and surveilling communications and defense industries. Fox Kitten’s activities are in turn, a product of a cooperation between two additional Iranian contract groups; APT33 specializing in monitoring and infiltrating the air and energy industries, and APT34/Oilrig.

We can assess that Pay2Key’s campaign’s objective was primarily to cause panic in Israel. The threat message the group published indicates that this campaign is one of propaganda with the purpose of striking fear into the hearts of Israelis and diverting attention away from Fox Kitten. This assessment is supported also by the fact that the message was published on social media, instead of just demanding ransom. The group further claims it was able to infiltrate “Alta”’s systems, a subsidiary of Aerospace Industries that develops and manufactures the Iron Dome.

In conclusion, cyber activity is an integral part of the ongoing conflict between Israel and Iran. Iran’s use of cyber contractors as proxies complements its use of military proxies in the Middle East. The possibility of Iran launching a cyber-attack on Israel’s Aerospace Industries’ systems while simultaneously launching a missile attack by Hezbollah, must leave those responsible for Israel’s security awake at night.

At this stage, Iran refrains from launching “paralyze” attacks on Israel’s vital systems, being content with targeted information-gathering and propaganda campaigns in order not to provoke a harsher retaliation from Israel. However, this strategy also has an exception; when Iran attempted to sabotage Israel’s water systems during this last year.

Israeli retaliation options in such a case and rapid detection of the source of attack, become more complex in cyber space where Iran’s proxies are decentralized and their lines blurred. To address the threat, Israel continues to develop and strengthen its cyber-offensive capabilities, but more importantly, its defensive capabilities.

This article was written by Mayan Sarnat, a research colleague of the Alma Center. She has a master’s degree in diplomacy and security from Tel Aviv University. Today, she is a senior analyst in the security field in a company specializing in intelligence research and national security.

One Response