By: Mayan Sarnat

Hezbollah’s communications architecture developed in accordance with its military development. It has grown more powerful and sophisticated and has expanded across increasing areas of Lebanon in accordance with Hezbollah’s growing need to securely transfer greater volumes of information and thwart and compromise Israeli activity.

As early as the 1990s, Hezbollah began using the existing Lebanese communications infrastructure for its internal use. At the same time, Hezbollah began building a communications infrastructure parallel to that of the Lebanese state for the use of the organization’s more sensitive communications. Hezbollah’s communications were both separate and interwoven in the Lebanese state’s communications system and soon after also into the global communications system.

Reports In 2007, asserted that Iran funded and improved Hezbollah’s new cellular infrastructure by building private cellular telephone networks that included high-frequency encrypted cells (“Iran telecom”). In a statement sent to the U.S. Embassy in Beirut, Lebanese Communications Minister Marwan Hamada wrote that the system was “a strategic victory for Iran since it creates an important Iranian outpost in Lebanon, bypassing Syria” … the value for the Iranians as strategic, rather than technical or economic. The value for Hezbollah is the final step in creating a [separate] nation-state. Hezbollah now has an army and weapons; a television station; an education system; hospitals; social services; a financial system; and a telecommunications system”.

How important is the independent communications network for Hezbollah? On May 05, 2008, The Lebanese government, led by Fouad Siniora, decided, among other things, to dismantle Hezbollah’s independent underground telephone network, which was based on Lebanon’s cable infrastructure placed inside the state’s communication ducts. The purpose of Hezbollah’s independent telephone network is to provide communications between Hezbollah headquarters throughout Lebanon.

Hezbollah’s response to these decisions was swift and aggressive. In a speech on 8 May 2008, Nasrallah declared that Hezbollah’s independent telephone communications network was one of Hezbollah’s main weapons and any harm to it was in fact a declaration of war on Hezbollah. A few hours after Nasrallah’s speech, Hezbollah operatives with the aid of Amal activists took control of west Beirut, besieged the international airport, laid siege on the Sunni community leaders center, headed by Saad Hariri, setting fire to the al-Mustaqbal network offices owned by Hariri and serving as his party’s mouthpiece.

That night, it appeared that Lebanon was in the midst of another civil war and that Hezbollah intended to take over Lebanon… Hezbollah was willing to “go all the way” if any internal Lebanese factors harmed or tried to harm any of its substantial interests, especially any of its security interests, even at the cost of another civil war in Lebanon. On 11 May 2008, the Lebanese government decided to overturn its decisions to dismantle Hezbollah’s independent telephone network.

If we conduct a modelling of Hezbollah’s communications infrastructure, we will notice a form of layered branches that will show that each branch has a number of nodes connected to a fiber optic line. There is no single node or branch that if hit, can cause the shutdown of the entire system. There is no central node for which most or all the branches connect, except perhaps for the official and visible Lebanese communications infrastructure. Therefore, severing Hezbollah’s communications would require the destruction of the entire Lebanese state telecommunications infrastructure.

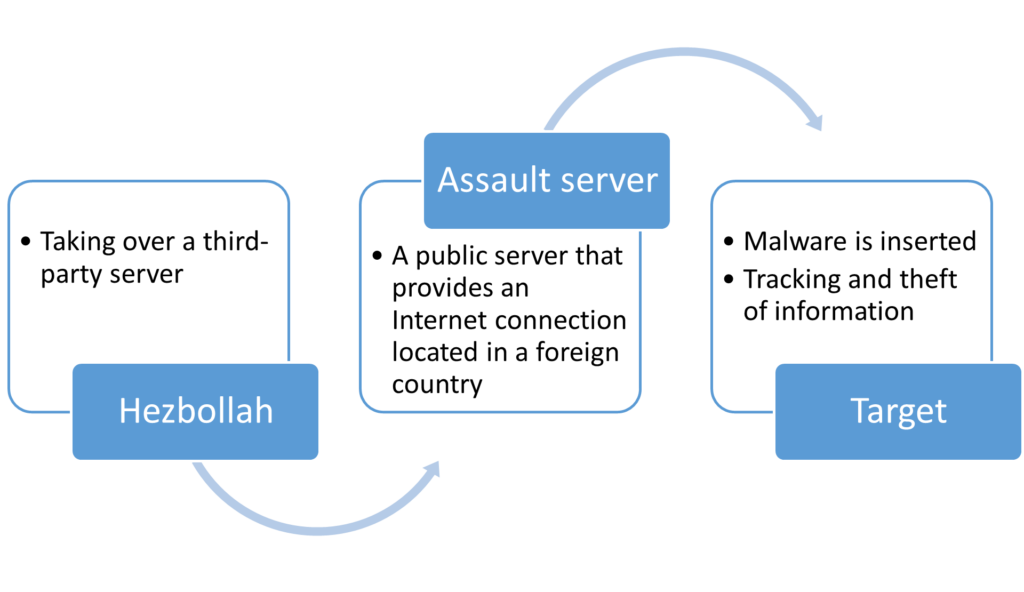

Hezbollah’s communications infrastructure continued and evolved and is now able to combine the Voice over Internet (VoIP) protocol (allowing voice calls to be made via broadband Internet connection instead of a standard phone line) with the fiber optic networks, built by Hezbollah, forming a fairly powerful communication architecture. Hezbollah uses this infrastructure in order to interface with global information technology infrastructures in order to generate strategic depth to its systems. In addition, this infrastructure enables the “hijacking” of servers in third-party countries for carrying out cyber-attacks while maintaining its anonymity.

Server takeover enables, among other things, the creation of virtual private networks (VPN) allowing Hezbollah to connect securely with Hezbollah elements around the world. For example, VPN networks function effectively in managing fundraising operations and logistics support. Hezbollah’s cyber-operators do not harm or disrupt the normal activities of the servers they hack into; rather, they are able to improve the dispersal and depth of their communication architecture without attracting attention. Unless alerted, the affected server owners function unknowingly as the basis for Hezbollah attacks against other elements.

Between 2012 and 2015, a scheduled attack campaign called the Volatile Cedar targeted individuals, companies, and institutions around the world. This campaign successfully penetrated multiple targets using various attack techniques, particularly planting customized malware. The purpose of the software, named by the attack group, “explosive”, was to gather information and track the target systems. A thorough investigation of the software led to the conclusion that the attack group originated in Lebanon. Based on the targets the modus operandi and resources required, the campaign was attributed to Hezbollah.

The attack group’s modus operandi was to infiltrate public internet servers by detecting vulnerabilities automatically and manually. After controlling the server, the attackers infiltrated the internal network even further and were able to carry out attacks such as sending malware and making it harder to detect their traces. The “explosive” software had passive collection capabilities as well as on-demand active capabilities. Once the software was installed on the target, the attackers were able to collect information that was transferred directly to the server they had commandeered.

Security contractors, telecommunications, and media companies along educational institutions were among the targets attacked. In about ten different countries, such “infections” were detected, including the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Turkey, Lebanon, and Israel. Although many of the technical aspects of the campaign were not considered sophisticated, it was activated regularly and successfully avoiding detection by an absolute majority of the end network devices. This success stemmed from a carefully planned and carefully managed operation that tracked the actions of its victims and responded quickly to events. The attackers chose only a handful of targets to prevent unnecessary exposure while new and custom-made versions were developed accordingly.

In January 2021, the source behind the 2012 to 2015 attack campaign was exposed. According to the Clear Sky Company (clearskysec.com), a group belonging to Hezbollah’s cyber network called “Lebanese Cedar” perpetrated the cyber-attack: Since 2015, the group has managed to operate “under the radar,” but another up-to-date campaign of the group has been unveiled. The current campaign has targeted systems and databases of hundreds of companies around the world, primarily in the telecom and infrastructure field, gathering intelligence and stealing data. The targeted companies are companies operating in the United States, Britain, and in the Middle East: Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, the Palestinian Authority, and Israel.

Another example of exposing Hezbollah’s attack servers was in the year 2018. The Czech Security Intelligence Service removed servers located in the Czech Republic used by Hezbollah operatives to infect mobile phone users around the world with malware. Hezbollah operatives created fake Facebook profiles, posed as women, and lured the chosen targets. The purpose of the action was to persuade the targets to install a correspondence app. on their mobile phone in order to continue a private conversation and thus actually run malware on the target’s mobile device. The servers hosting the malware were found in the Czech Republic, but also in other parts of the European Union and the United States. The campaign targets were men from the Middle East, but also from Central and Eastern Europe.

Today, Hezbollah controls the Ministry of Communications in Lebanon, placing the management of the industry under their direct control, while ousting the two private companies (Alpha and Touch) that filled this role on behalf of the state. The annual profits from the communications industry could amount to about a billion dollars, making it a very significant asset. Under the responsibility of Hezbollah operative Hussein Hajj Hassan, head of the parliamentary committee for information and communications, Hezbollah is preparing a comprehensive national telecommunications strategy that matches its objective. It can be estimated that Haj Hassan will ensure the existence and expansion of the communications infrastructure that will enable the execution of such server attacks.

Hezbollah’s communications infrastructure separates it from other Lebanese organizations by the scalable, systematic deployment of the communications architecture. While the development of the cyber capabilities that the infrastructure enables adds an additional dimension of strategic depth to Hezbollah’s communications, the real question is less of an absolute ability to communicate, and more of a secure communications infrastructure that can support military operations in real time.

Some of the examples presented in this article are from previous years. However, they can demonstrate the trend and the activity that characterizes Hezbollah today. As the leading proxy in Iran’s radical Shi’ite axis, Hezbollah received tools and training from Iran in the cyber field. In this area, Iran’s deniability in using Hezbollah as a proxy for regional intervention is even more powerful. It can be estimated that Iran will continue to use Hezbollah’s cyber array for its own purposes, beginning with espionage, as illustrated in the cases of Volatile Cedar and the Czech Republic, through abusive actions such as denial of services cyber-attacks to institutions in countries such as Saudi Arabia and Israel.

This article was written by Mayan Sarnat, a research fellow at the Alma Center. She holds a Master’s degree in Diplomacy and Security from Tel Aviv University. Currently serves as a senior defense analyst at a company engaged in intelligence and national security research.