Article by: Teddy Sapir

The ongoing political crisis in Lebanon has led the country to social, economic, and medical chaos. The situation was intensified by the explosion a year ago in the port of Beirut in August 2020. Israel proposed humanitarian and medical assistance to Lebanon. However, the Lebanese government ruled out any offer of help.

Israel has offered assistance to Lebanon in the past and even today we are ready to act, and to encourage other countries to extend a helping hand to Lebanon so that it will once again flourish and to emerge from its state of crisis.

— בני גנץ – Benny Gantz (@gantzbe) July 6, 2021

On July 6, 2021, Israel forwarded an official offer of assistance to Lebanon through UNIFIL. The Israeli Ministry of Defense stated that in light of the dire economic situation in Lebanon, and in light of Hezbollah’s attempts to bring Iranian investments into Lebanon, the Minister of Defense, through the liaison factors in the IDF and UNIFIL, made an official proposal offering the transfer of humanitarian aid to Lebanon.

The Lebanese transitional Prime Minister, Hassan Diab, considered Hezbollah’s “marionette,” said Lebanon was on the verge of collapse and social disaster. He stressed that the transitional government could not advance any economic solution with the IMF in implementing a financial recovery plan. Diab warned against the international community’s intentions (led by France and the United States) to link the establishment of a government in Lebanon to humanitarian aid intended for Lebanese civilians. In reality, Diab, in his remarks, thwarted Israel’s proposals as well.

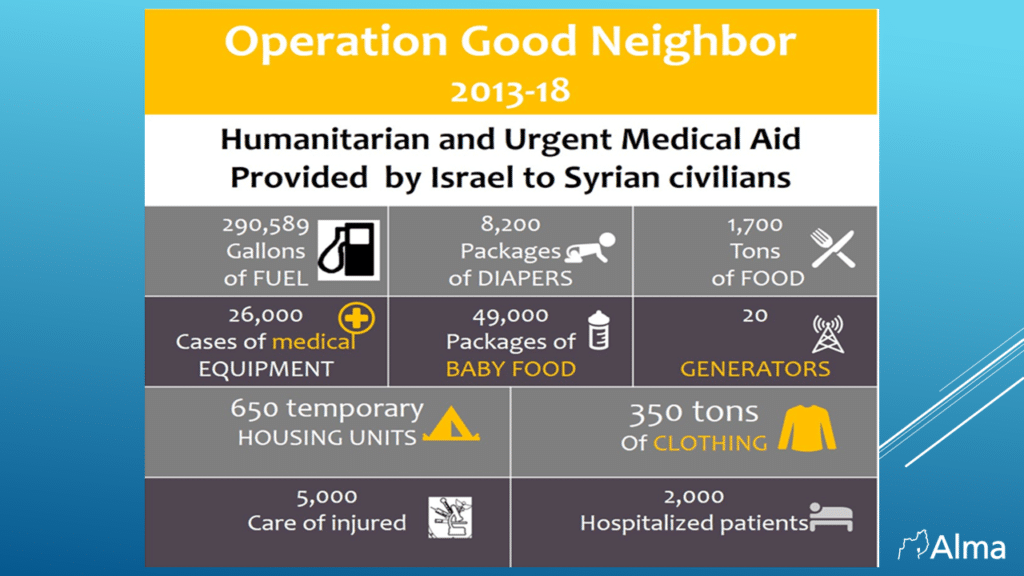

As of now, it is difficult to assess whether Lebanon will emerge from the immense crisis that it currently faces. If not, will the state of Lebanon fall apart and, in fact, be divided into cantons in which each ethnic community will take care of itself? Could the “Good Neighbor” project that operated alongside the Israel-south Syrian border between 2016 to 2018 be relevant vis-à-vis southern Lebanon in the event of the collapse of the Lebanese state? Would the State of Israel be able to operate alongside south Lebanon as it did in the mid-1970s? (from 1976 –in a project called the “Good Fence”), or as during the First Lebanon War and throughout the IDF’s period in south Lebanon? (1982-2000). During these periods, Israel established a civilian administration responsible for the civilian treatment of the Lebanese citizens under its jurisdiction.

There is no doubt that the situation in Lebanon has implications on Israel in general and on Israel’s northern border in particular. Exiting the crisis by forming a government that Hezbollah controls (similar to the former government) will strengthen Hezbollah. This is in addition to the possibility of introducing Iran as Lebanon’s great savior, a step that will lead to greater control of the organization over Lebanon and its institutions, and the commitment of the Lebanese government to Iran, and basically establishing a real Iranian foothold in Lebanon.

On August 3, the Hezbollah-affiliated daily Al-Akhbar reported that Nasrallah stated that the decision to import materials from Iran had been made and that a group of Hezbollah members was in Iran working on completing arrangements to transfer fuel and diesel from Iran to Lebanon by land or sea.

The collapse of the Lebanese state could lead to several possibilities, from Hezbollah taking over state institutions, alongside a collapse and the start of civil war, the division into areas of control based on ethnicity and interests, and a population seeking an address for assistance.

We estimate that the direct impact on Israel is an escalation of the security situation.

Yet, the question arises as to whether there is potential for a renewal of the relationship with the Lebanese population and the resumption of humanitarian and medical assistance.

Projects such as the “Good Fence” in southern Lebanon from 1976 until the IDF left Lebanon in 2000, or the “Good-Neighbor” project on the Israeli- south Syrian border from 2016 to 2018.

During the periods described above, both the Lebanese and Syrian central governments collapsed. Therefore the aid requests to Israel came from local officials. This came after the local population reached their endurance limit from a humanitarian and medical point of view and after they felt threatened from a security perspective. In both cases, no Israeli initiative was taken that could indicate Israeli intervention, which inevitably could lead to disapproval and opposition from the local population.

In the two previous cases (the “Good Fence” project and the IDF’s period in southern Lebanon and the “Good Neighbor” project in south Syria), the situations were different. During the establishment of the “Good Fence” project in 1976, the local Lebanese population in southern Lebanon, both Shiite and Christian, suffered from Palestinian organizations violence and were essentially cut off from the central Lebanese government, turning them to Israel for help with the intention of receiving medical assistance and then extensive humanitarian aid that had developed over the years.

The “Good Neighbor” project in southern Syria in 2016 was also different. The local population, most of whom are Sunni Muslims, longed for help after being attacked by both the Syrian regime itself and extremist Salafist organizations such as ISIS. Therefore, the appeal to Israel was only natural. This was also due to the inability of Western and Arab countries to provide assistance to the civilians themselves since their contribution focused on military aid to the opposition factions.

Therefore, in the previous two events, the population was open to medical and humanitarian aid. There were not many pockets of resistance to the direct contact with Israel and its assistance.

Compared to these two previous events, the situation in Lebanon today is fundamentally different. Although the central government may collapse, we estimate that the Shi’ite population is unlikely to turn to Israel for assistance. Hezbollah’s power in south Lebanon is immense. Most of the villages in south Lebanon are pro-Hezbollah Shiite villages, where the organization’s influence and power are enormous. In addition, the Shiite population receives close assistance from the organization through Hezbollah’s aid, welfare, and medical organizations, which maintain its civic “base.” Beyond the practical issue, there is also the matter of the perception issue. Hezbollah terrorizes Lebanese citizens with an emphasis on the Shiite population.

It is possible that Christian communities close to the Israeli border (such as Marjayoun, Qlayaa, Rmeish, ʿAin Ebel, Debel) and Sunni and Druze Muslim areas that live far from the Israeli border will feel threatened. In light of this, they may seek Israeli assistance in an exceptionally extreme scenario not only because of the dire humanitarian situation but also for fear of their safety and security. However, in our opinion, Hezbollah would forcibly prevent any physical contact in the border area, not permitting it, even by opening fire on any such attempt, or, alternatively, thwarting any transfer of such aid when it succeeds and enters Lebanese territory.

Hezbollah had promoted over the years two narratives through its propaganda campaign:

- “victory on the first day of liberation” when the IDF withdrew from southern Lebanon in May 2000 (the second victory is Hezbollah’s victory in the battles of al-Arsal and al-Qalamoun in 2016 against Syrian opposition elements).

- “divine victory,” according to Hezbollah, in the Second Lebanon War in July 2006.

Both narratives constitute a background that will prevent and compel the population not to seek any assistance from Israel. They will fear that they will be portrayed as collaborators with the Zionist enemy on the one hand and fear for their life on the other hand.

Hezbollah will not allow the Lebanese state to receive assistance from Israel, even if it is a local initiative of the population residing close to the border fence. Therefore, in our opinion, the likelihood that a “good neighbor” project will be re-established in the southern Lebanon region, in one form or another, is extremely low. If the Lebanese population does turn to Israel for assistance, Israel has the ability, knowledge, and experience, alongside Hezbollah’s possible threat, to assist them.

It should be noted that Israeli intervention and assistance may also act against Israel, as it will give Hezbollah legitimacy to launch an offensive in light of Israel’s intervention in Lebanon’s affairs, proving the organization’s claim for years that Israel has territorial ambitions in Lebanon and that the “resistance” is the “protector of Lebanon”.

Israel, for its part, can diplomatically influence western countries, such as the United States and France, which lead the solution and aid to Lebanon. It is important to link the international assistance to reducing Hezbollah’s power and preventing an Iranian takeover attempt and foothold. However, it is doubtful that the power of the Hezbollah state, which actually controls the Lebanese state, can be reduced.

Teddy Sapir is a resident of northern Israel and a research fellow at the “Alma” Center. He is a Ph.D. student in Middle Eastern history at Bar Ilan University. His research is focused on the Syrian and Lebanese arenas. Mr. Sapir holds the rank of Lt. Col. (Res.) in the IDF’s Intelligence Division.