Syria is not considered a wealthy nation when it comes to natural resources, particularly when it comes to oil and natural gas, and its oil is considered low-grade. Over the past few years, there has been a struggle between Russia and Iran over the Syrian oil and natural gas infrastructure as part of their “influence race” in Syria. Syria’s oil and natural gas are not the point of the struggle. However, they are primarily a tool that will allow their owner to control Syria’s energy infrastructure. Whoever controls its infrastructure will have regional and international influence.

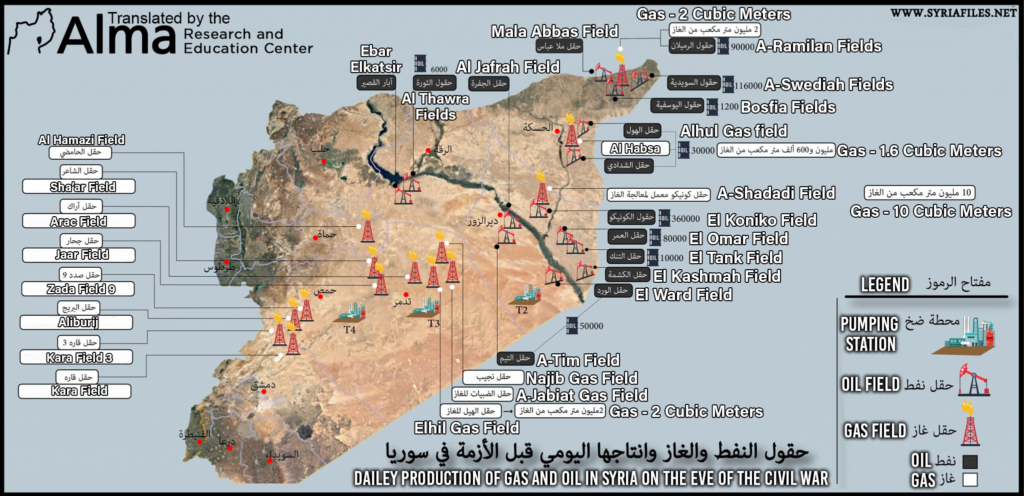

Before Syria’s civil war began in 2011, Syria’s daily production rate was approximately 380,000 drums of oil and 24 million cubic meters of natural gas (Syria’s daily demand for oil is 258,000 drums). At the start of the civil war, many oil and natural gas fields fell into the hands of different militias and rebel forces, mainly ISIS, who has had control of the oil and natural gas fields in northeast Syria for a long time: the Deir ez-Zur area, Palmyra, and the Aleppo area. ISIS’s lack of knowledge and ability to maintain energy infrastructure caused the oil and natural gas fields’ production rate to drop to an all-time low.

According to an IMF report from 2016, Syria’s 380,000 oil drums post-civil war production rate dropped to an estimated 80,000. Syria’s oil reserves are estimated at approximately 2.5 billion drums, with 75 percent in Deir ez-Zur’s fields. According to the report, natural gas production in the fields of Al Hasakah, Rmelan, and al-Jibasa is estimated at 600,000 cubic meters per day. Seven fields in the Palmyra area can produce more than 7 million cubic meters per day, and the rural fields of Damascus can produce approximately 1.5 million cubic meters per day. In 2008, a report issued by the United Nations estimated Syria’s natural gas reserves at 7.5 million cubic meters.

When ISIS was defeated in 2017-2018, the fields were recaptured by the forces controlling Syria today: the Kurd “Syrian Democratic Forces” (SDF) militia, backed by the US Army in northeast Syria (Al Hasakah and Deir ez-Zur), the Russian Armed Forces and the militias subject to it, including the Assad regime’s army, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, and the Shiite militias subject to it, and of course Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Even today, the oil and natural gas fields need protection from ISIS, scattered over various areas, primarily in northeast Syria. Ironically, Syria, which is already in a dire economic state, pays protection money in the form of oil and natural gas to foreign forces who “defend” it, mainly Russia and Iran’s radical Shiite Axis.

Agreements between Russia and Syria were signed as early as 2017 when the Syrian government hired a Russian security company to defend the oil and natural gas facilities from ISIS in exchange for 25 percent of the fields’ profits. Russia, via several companies (Mercury, Vlada – STG, and others), then acquired rights to the fields in the rural area of northern Damascus, the Kara and AlBurij, and the four fields in Palmyra and east of Holms. These agreements included rehabilitating oil wells and infrastructure, as well as consultation and guidance of the workforce. These agreements were estimated at 40 million dollars.

The Kurds (“SDF”) also do business with the Syrian government. The Kurd-controlled oil is refined in Syrian-owned refineries in Homs and Banias. According to reports, the Kurds receive 75 oil drums for every 100 drums of crude oil they transfer to Syria.

The Sha’ar field in the Aleppo area, which includes processing and refining infrastructure and is considered one of Syria’s most extensive fields, is a prominent example of the struggle between Russia and Iran over the oil and natural gas fields in Syria.

Syria’s neighbor, Lebanon, is in a severe energy crisis. Hezbollah saw an opportunity to satisfy both Lebanon’s Shiite populations and its own energy needs with readily available Syrian oil.

Hezbollah entered the Sha’ar fields in the summer of 2021, and with the Russian and Syrian authorization, began to work them using engineers explicitly hired for the task. Russian forces have been guarding the field since its capture; some of their soldiers were even killed in ISIS attacks in 2021.

The moment Hezbollah began working the fields, convoys, sometimes even up to 100-oil-tankers-long carrying hundreds of millions of liters of oil, began making their way to northeast Lebanon.

At the beginning of 2022, Russia decided to expand its control of the area’s oil and natural gas fields. In February 2022 (before the war in Ukraine), Russia notified the IRGC and Hezbollah authorities in the Sha’ar field that Hezbollah would not be able to supply Lebanon from then on with the quantities it had been providing until then. Most of the fields’ yields will be transferred to Tartus refineries under total Russian control. Several days later, the IRGC responded by blocking the transport of all oil tankers from the field, including those bound for Tartus. They told the Russians not to interfere and that the oil supplied to Hezbollah is part of previous agreements between Iran and Assad’s regime.

According to some reports, it is possible that Russia’s move was made because of Russia’s behind-the-scenes agreement with Israel and the United States, in which the latter states agreed to decrease the number of strikes in areas north and west of Syria which are home to Russia’s central bases in Syria.

These reports match Russia’s behavior since the beginning of 2022. Russia began to increase its efforts in the “influence race” against Iran in Syria, both in military and civilian terms. However, it seems as though Russia has ceased its efforts since its war with Ukraine began.

Iran uses its control of the Al-qaim / Al-bukamal border crossing between Iraq and Syria, as well as its influence on the Iraqi oil and natural gas export agreement, to apply pressure on other states. Iraqi natural gas and oil are transported via this border crossing and make their way to Syria’s ports in Banias, Tartus, and Latakia.

This is not Russia’s and Iran’s first confrontation in Syria as part of their “influence race”. The Assad regime is in a predicament and is trying to operate under the two states that serve as its protector and benefactor.

There is a claim that Syria’s oil and natural gas are not Russia’s and Iran’s objective (and possibly not the United States, which protects the oil and natural gas fields controlled by the Kurds in northeast Syria). Syria’s oil is of the lowest quality because it contains sulfur. The two states’ desire to control Syria’s oil and natural gas is mainly to enable them to control Syria’s energy infrastructure.

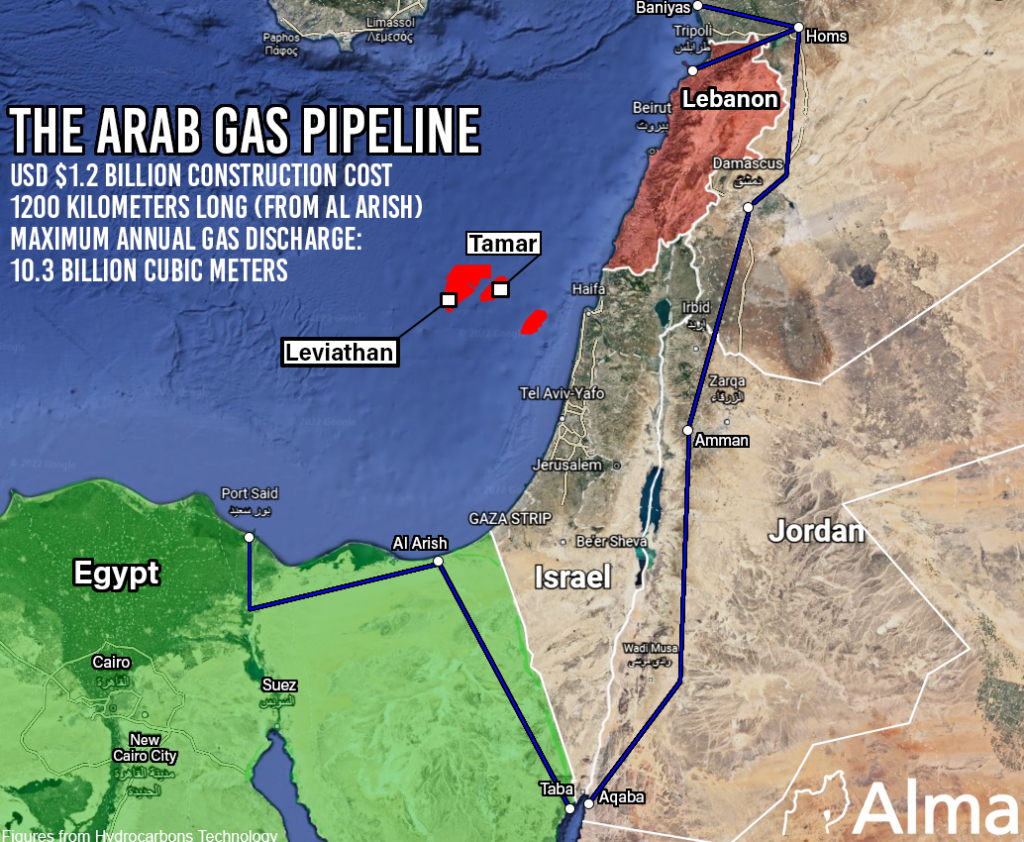

Controlling infrastructure will allow them to influence regional and international interests. For example, parts of the Arab natural gas pipeline connecting Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Turkey to Europe are dependent on Syria’s energy infrastructure. Shortly, this pipeline will transfer natural gas from Egypt (which, according to many reports, is supplied by Israel) to Lebanon via Jordan and Syria.

(See our article from January 2022 – https://bit.ly/3NiMvHv).

This is in accordance with American and European interests and is funded by them. On June 21st, an agreement on supplying natural gas was signed between Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon. Russia and Iran will take extraordinary measures to influence American and European interests.

Syria’s energy infrastructures’ geographical location makes them a vital bottleneck between Africa, Asia, and Europe. Therefore, Syria is less a state with energy reserves and more a geographical passage between the Middle East and Europe. On this matter, Russia’s and Iran’s interests are apparent. For Russia, Syria is another foothold in the Middle East at the expense of the United States and is a sanctions-bypassing lifeline considering its war with Ukraine. For Iran, Syria, after Iran’s signing of the Iran Nuclear Deal and the uplifting of international sanctions imposed on it, will allow it to export oil and natural gas to Europe via the ground infrastructure and can even serve as an alternative to Russia’s energy supply which Europe has blocked off as a result of Russia’s war with Ukraine.