By: Yaakov Lapin and Sarit Zehavi

The fall of Bashar al-Assad and his Alawite regime in Syria in December 2024 triggered a revolution in the geopolitical landscape of the entire Middle East and ignited a complex power struggle among regional and global actors seeking to secure their strategic interests in Syria, while promoting conflicting ideologies.

The recent events between the jihadist forces of Al-Julani (Ahmad al-Shara) and the Druze in southern Damascus and Sweida, and the Druze demand for Israeli involvement in their defense, are just recent examples of how quickly reality is changing in the Syrian arena and its impact on neighboring arenas. In this article, we will review the interests of the various players in Syria.

Russia

Russia’s ability to maintain its presence in Syria has now become uncertain, with its forces already stretched thin on the European front due to its ongoing war in Ukraine. Russia’s main goal in Syria is to preserve its military foothold, especially at the Tartus naval base and the Hmeimim airbase, both located in the Alawite region of northwestern Syria. These facilities are critical to Moscow’s regional and global ambitions, as they provide a strategic gateway to the Eastern Mediterranean and allow Russia to project power in the Middle East, counterbalancing American influence.

Moreover, it is unclear to what extent Russia is committed to helping reestablish Iranian influence in Syria, as Iran is supplying Russia with weapons in its war against Ukraine.

It is worth noting that Alawite civilians and former Assad regime members who fled the massacre carried out by Islamist gunmen from al-Shara’s forces in mid-March fled to the Russian airbase in Hmeimim.

The overthrow of Bashar al-Assad, Russia’s long-standing ally and protégé, in December 2024, damaged Russia’s long-term influence in the region, since the Sunni Islamist rebels who now control Syria were previously targets of Russian airstrikes, particularly in the Idlib enclave.

Nonetheless, Syria’s new government, led by Ahmad al-Shara, signaled its willingness to negotiate with Russia. Syria’s new defense minister, Murhaf Abu Kasra, stated that Russia may be allowed to maintain its bases if it provides economic and military aid. Moscow, recognizing the changing dynamics, is adopting a pragmatic approach to ensure a continued foothold in Syria.

From Israel’s perspective, there is debate over what is preferable. Russian weapons have appeared in Hezbollah’s stockpiles in southern Lebanon in large quantities, having arrived via Iran and the Assad regime. On the other hand, some voices in Israel assess that Moscow is unlikely to continue actively arming Hezbollah now, since this would contradict the wishes of the new Sunni regime in Damascus and undermine Russia’s own efforts to maintain a presence in Syria.

Iran

The fall of Assad was a severe blow to Iran’s massive investments and presence in Syria. For years, Tehran invested about $30 billion to support Assad’s regime and used Syria as a vital land corridor to transfer weapons to Hezbollah in Lebanon and to deploy Shiite militias from Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Syria played a central role in Iran’s strategic plans against Israel, both in terms of missile threats (“the ring of fire”) and a ground invasion threat under the banner of “Unity of the Arenas.”

However, the new Sunni Islamist government in Damascus openly opposes Iranian Shiite influence and sees Tehran as a religious and sectarian enemy. This disruption of weapon transfer routes and the loss of a direct military threat to Israel are major setbacks for Iran’s regional strategy. This also undermines Iran’s vision of turning Syria into a frontline against Israel alongside Lebanon.

In response, Iran is likely shifting its approach, and seems to be transferring its support to the Alawite communities while exploring diplomatic options with the new government. Despite its ideological commitment to the “Axis of Resistance” led by Hezbollah, Iran now faces a dual challenge: stopping Turkey’s growing influence in Syria and adapting to a fragmented political system in which it lacks a clear military ally but faces Sunni enemies and neutral actors, from Iran’s perspective, like the Kurds.

Iran will seek ways to undermine al-Shara’s rule and regain influence in parts of Syria. Simultaneously, it will try to “buy” from al-Shara strategic controlling anchors that once enabled its land smuggling corridor in Syria.

Hezbollah

Hezbollah has long relied on Syria as a critical logistical hub for transferring Iranian, Russian, and Syrian weapons. It also served as a strategic reserve force for Assad’s regime, working closely with Iran’s IRGC. For Hezbollah, Syria was a primary battlefield for ground operations alongside Assad.

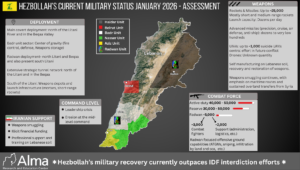

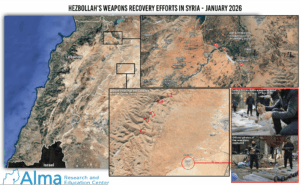

The collapse of Assad’s government has severely disrupted Hezbollah’s weapon supply routes to Lebanon, leaving the organization more isolated than ever. While Hezbollah maintains its ideological commitment to oppose Israel, it now faces significant operational challenges.

To compensate, Hezbollah is seeking new weapons routes through Lebanon’s air and seaports and is exploring alternative smuggling networks. One option is to use Turkish territory, as flights from Iran to Syria and Lebanon have ceased.

Nevertheless, Hezbollah has not entirely abandoned Syria. Sporadic clashes with the new regime near the Lebanese-Syrian border indicate that both sides see this area as strategically and economically vital for smuggling weapons, money, oil, and drugs.

Turkey

Turkey sees post-Assad Syria as a once-in-a-generation opportunity to expand its influence. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has long sought to restore Turkish hegemony through a radical neo-Ottoman Islamist vision, using Islamist proxies and establishing military bases on Syrian territory. Assad’s collapse created a power vacuum that allowed Turkey to dominate most of Syria, except for the south, and shape the new Syrian political landscape to its advantage.

Beyond religious motivations, in this framework, Turkey’s primary interest is to limit Kurdish military capabilities. Kurds, an ethnic minority divided between Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, aspire to establish their own state — viewed by Turkey as a strategic threat that would lead to the loss of substantial territories. Kurdish militias on the Syrian-Turkish border are viewed by turkey as a security threat, including potential terror attacks.

Thus, Ankara’s strategy has focused on suppressing the Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) by supporting Sunni Islamist factions, particularly HTS (Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, led by Ahmed Al-Shara) and even more closely the Syrian National Army (SNA), which received Turkish military and economic support. Turkey aims to disarm the SDF and push them away from its border.

On March 10, the new Syrian regime signed an agreement with the SDF. Al-Shara and Mazloum Abdi, SDF’s commander, signed the deal. Under this agreement, Kurdish forces and institutions will be integrated into Syria’s new state and army structures. The agreement guarantees Kurdish rights, representation, and refugee return under regime protection, while handing border crossings and border control to the new regime. Control over energy infrastructure may also be transferred later.

The agreement does not specify which areas refugees will be allowed to return to, including areas seized by Turkey and the SNA in northern Syria.

Turkey’s position on the agreement and its role in drafting it remain unclear. The deal states that the regime will protect displaced persons, but it is uncertain whether this is coordinated with Turkey and the SNA or whether al-Shara will act against them if they do not respect the deal.

Another Turkish interest is returning Syrian refugees to Syria — a project already underway. In late December 2024, Turkey reopened the Yayladagi crossing, parallel to Syria’s Kassab crossing, to enable refugee return. Since then, thousands of refugees have returned, but the numbers remain small compared to the 3.3 million Syrians living in Turkey.

With the removal of pro-Iranian militias and Russia’s weakening influence, Turkey has become the dominant external power in Syria, replacing Iran. Erdogan’s ambitions extend beyond Syria, as reflected in his harsh rhetoric against Israel, including public calls to Turkish youth to prepare for future battles over “Al-Aqsa” in Jerusalem and his prayer at the end of March calling on Allah to “destroy Israel.”

Turkey’s growing military-industrial capabilities, particularly in drones and missile systems, pose a new strategic concern for Israel. Ankara’s influence over Syrian factions could result in a new Turkish-backed proxy force directly threatening Israeli interests.

Recently, it was reported that Turkish warplanes confronted Israeli jets over Syria during Israeli strikes in late April, and appeared before them, face to face. International media reported that at the time, Israel attacked pro-Turkish militia sites several times, in multiple locations across Syria.

Turkey’s NATO membership complicates matters, allowing Erdogan to pursue an independent foreign policy that strays from the Western positions, while maintaining formal ties with the alliance. However, it also provides an opportunity for American pressure on Turkey to avoid threatening Israel.

Israel

Israel’s top priority in Syria is to prevent hostile Sunni Islamist and Turkish forces from establishing a foothold that could threaten its security. The threat scenario essentially involves replacing the radical Shiite axis with a radical Sunni one. Israel is suspicious regarding the ideological commitment of Syria’s new regime to extreme Islamist principles. Although the regime takes pragmatic positions to gain international legitimacy, its leadership and many of its armed forces are rooted in extremist views. This raises concerns that Syria could become a new Sunni jihadist front, directly or through Turkish-backed proxies.

Following Assad’s fall, Israel increased airstrikes and ground operations, particularly in the Golan Heights and southern Syria, to prevent the new regime from seizing the former regime’s weapons. This includes chemical weapons, advanced air-defense systems, anti-aircraft guns, and various military assets.

Recently, Israel attacked former Assad regime military sites now reportedly operated by the new Sunni leadership. Israel also took control of the buffer zone along the border, where the IDF established a security belt with nine outposts to protect Israeli communities in the Golan Heights against any threat – Sunni, Shi’ite, or other. This move is a direct lesson from the October 7 events.

This area has not been demilitarized since Syria’s civil war in 2013, when multiple forces operated there, including the Syrian army, ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and various rebel groups. After losing to Assad’s forces in 2018, pro-Iranian militias and the Lebanese Hezbollah took over the area.

Israel has come to see an alliance with the Druze in southern Syria as a strategic way to push back against Islamist Sunni forces near the Golan border.

Recognizing the threat to minorities under Al-Shara’s forces, who possess extremist ideology, viewing them as infidels with no right to exist, Israel has positioned itself as the protector of the Druze in southern Syria. Through economic opportunities and security guarantees, Israel has built alliances and ensured a friendly presence along its northern border amid the ongoing chaos in Syria.

On May 2-3, this policy escalated significantly. Israel used substantial air power to defend the Druze sector after it was attacked by jihadist forces, some reportedly aligned with Al-Shara’s regime.

Following a warning strike near the Presidential Palace in Damascus, the IDF launched a large wave of airstrikes targeting military sites, anti-aircraft guns, and surface-to-air missile infrastructure across Syria. Syrian media reported over 20 Israeli strikes in Damascus, Hama, Daraa, and Latakia.

More than 20 injured Syrian Druze civilians were evacuated by the IDF to hospitals in northern Israel. The IDF also deployed forces in southern Syria to prevent hostile elements from entering Druze villages and provided humanitarian aid.

About 150,000 Druze live in Israel. Israel’s commitment to defending Syria’s Druze poses a difficult dilemma regarding the level of military involvement required, especially given its multiple security challenges elsewhere.

Still, Turkey’s involvement in Syria is the most troubling potential threat. Turkey’s entrenchment presents a new challenge, especially if Turkish-backed jihadist factions obtain advanced or Western weapons and turn them against Israel.

The United States

Recently, President Trump announced his intention to withdraw American forces from Syria. There is already a drawdown and redeployment, mainly in northeastern Syria (Deir ez-Zor – al-Hasakah).

The U.S. maintains a force of about 1,000 troops in Syria, mainly to support Kurdish forces and prevent ISIS’s return. Washington’s policy remains cautious, supporting a transition to stable and moderate Syrian governance while gradually reducing its military presence. Sanctions remain an American tool to pressure the new regime toward reform.

However, with Turkey now the dominant external force, the U.S. faces challenges balancing its alliance with the Kurds against Ankara’s regional ambitions.

Trump does not seem to value the Kurdish alliance and sees them more as a burden, despite their critical role in fighting ISIS and acting as a moderate, pro-Western potential buffer against Iran.

The U.S. also plays a diplomatic role mediating between rival factions. Though it does not directly intervene in Syria’s transition, Washington seeks outcomes aligned with its broader regional interests. The question remains whether the U.S. will oppose Turkish expansion or allow Ankara to shape Syria’s future unchecked. An American withdrawal would mainly benefit Turkey and severely harm the Kurds.

Meanwhile, Al-Shara continues using media and meetings with Western politicians to convey messages to the U.S. In a meeting on April 24, he told Republican congressmen Cory Mills (Florida — considered close to Trump) and Marlin Stutzman (Indiana) that he is open to joining the Abraham Accords and establishing relations with Israel. However, he reportedly has demands: Israel must stop striking Syria, Syria must remain united, and — perhaps most problematically for Israel — a settlement must be reached regarding Israeli military presence in Syria, including Mount Hermon and the buffer zones.

Jordan

Jordan’s main concern in Syria is border stability and preventing extremism from spreading into its territory. Hosting a large Syrian refugee population strains Jordan’s resources, so it focuses on conditions for future returns and reviving trade routes. Jordan is also deeply concerned about smuggling, especially drugs and weapons.

To secure its borders, Jordan continues cooperating with the U.S. and other regional partners. The rise of a Sunni Islamist government in Syria introduces new risks, and Jordan fears potential radicalization that could threaten its internal security.

Accordingly, Al-Shara’s visit to Jordan on February 26, during which he met with King Abdullah, can be seen as an attempt by Jordan to hedge risks and gather information on its new neighbor. Jordan remains suspicious and deeply worried about the Sunni Syrian revolution’s impact on domestic stability, especially in its battle against the Muslim Brotherhood, which also seeks to overthrow Jordan’s regime.

Conclusion

Recent events and the regime change in Syria have reinforced the country’s role as a playground for larger powers, with every event inside Syria resonating beyond — even reaching Europe.

Many European states seek to establish ties with Syria’s new leader and lift sanctions, partly to encourage refugee returns and profit economically from Syria’s reconstruction. However, this could be dangerous. After all, this new regime is rooted in radical Sunni Islamist ideology and must not be given legitimacy to raise a new generation of jihadists that would threaten both regional and global security.

What starts in the Middle East rarely ends there.