Syrian refugee camp in the town of Ghazze in the Lebanese Beqaa (picture from 2020)

The civil war in Syria in 2011 led to many refugees fleeing the torn and bloody country. From the outbreak of the war to the present day, the number of refugees has reached about 5 to 6 million people. The refugees reached neighboring countries such as Jordan, Turkey, Lebanon, and even Iraq, and about a million refugees reached European countries.

The flow of Syrian refugees to Lebanon began in March 2011, and over the years, their number has risen to hundreds of thousands to an estimated 1.5 million Syrian refugees residing in Lebanon. About two-thirds of the refugees are registered and documented with the United Nations refugee agency; since May 2015, the Lebanese government has banned their registration. In other words, the refugees comprise more than 20 percent of Lebanon’s population of about 7 million people.

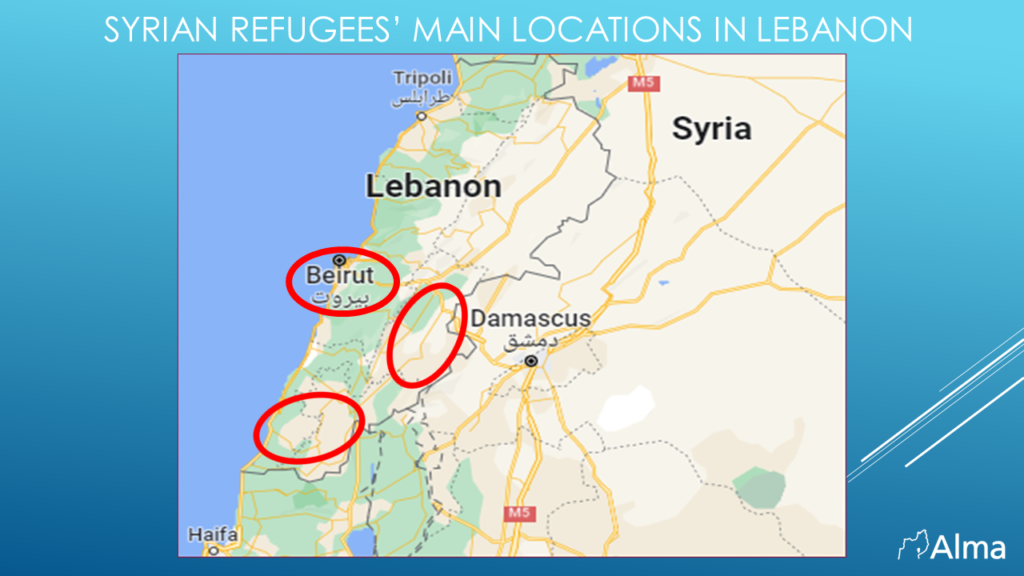

The Syrian refugees were concentrated in geographical areas, most in the Elbaka, some in northern Lebanon, Beirut, and south Lebanon. The Lebanese government’s policy towards them is that they dwell in Lebanon without any legal status, imposing severe restrictions on their movement, including threats of arrest, and prohibiting their employment in construction, agriculture, and cleaning; therefore, most of them do not receive work permits. About 80 percent of them live below the poverty threshold. The Lebanese state has reservations about establishing refugee camps in light of its bitter experience with the Palestinian refugees in its territory, which remain stateless residents of the country, constituting a burden on Lebanon.

Refugees in Lebanon have imposed great difficulty on the Lebanese state, which is already in an economic crisis. The difficulty is embodied in social and political tensions and security concerns of the potential spillover of global jihad into Lebanon, which could once again provoke a civil war in Lebanon. The refugee’s placed a great burden on the country’s infrastructures, water reservoirs, health system, social assistance, and sanitation matters. UNHCR and the UN system have begun to assist the many refugees who have flooded Lebanon, but their benefit has been minor.

Despite the Lebanese state’s prohibitions, there has been an exploitation of Syrian refugees who are desperate for sources of income at a particularly cheap price within Lebanon. Of course, the direct impact was on young Lebanese who could not find jobs for a reasonable income and were replaced by Syrian refugees. This has created severe unemployment among the Lebanese population. Lebanese politicians took advantage of the refugees’ presence and blamed them for the country’s difficult economic situation. At the same time, the attitude of the Lebanese population towards the Syrian refugees was harsh and hostile, bringing on disputes and violent confrontations.

Throughout the civil war in Syria, the Lebanese government tried to reduce the flow of refugees, but without success. With the (alleged) end of the civil war in Syria at the end of 2018 and to this day, Syrian refugees are in no hurry to return to Syria. In Lebanon, they do not have freedom of movement, and there is limited access to medical, educational, and nutritional services, making few refugees want to return to Syria. Their failure to return to Syria is due to several reasons. Fear for their lives from the Syrian regime, as perhaps some will be perceived as supporters of the opposition against the Syrian regime, reports of arrests and torture of refugees who have returned, inability to return to their homes because they were completely destroyed, or they have no proof that these are indeed their homes, destruction of the country’s infrastructures, fear of living conditions in Syria, lack of the guarantee of employment, lack of nutrition, medical and economic security, fear of local insurgent cells operating within Syria against the Syrian regime.

Over the years, Lebanese politicians have made statements against the refugees and the need to send them back to Syria. For example, Tamam Salam, former Lebanese prime minister, called as early as 2014 to take strong action against the refugees. These voices intensified after the end of the civil war in late 2018. In July 2018, then-Lebanese Interior Minister Nihad al-Mashnouk called for the return of the refugees to Syria. Among those calling for the return of the refugees was President Michel Aoun. His son-in-law Gebran Bassil, who served as minister of communications in September 2016, speaking at the Maronite Association conference, called for the return of the Syrian refugees to their country, stating that their return is a key part of finding a political solution in Syria.

In March 2017, Lebanese President Michel Aoun declared that Lebanon was dealing with the refugee’s negative consequences on Lebanon’s security, and social and economic issues, calling on European countries to help send the refugees back to their homes in Syria. In July 2017, Gebran Bassil, then foreign minister, again called for the return of the refugees to Syria and for implementing Prime Minister Tamam Salam’s plan, which includes several restrictive measures on the refugees. These measures intended to make the refugees’ lives in Lebanon difficult, encouraging them to return to Syria. On May 30, 2018, Patriarch Al-Ra’i, the head of Lebanon’s Maronite community, called for a solution in Syria, as refugees and displaced persons influence Lebanon’s status and change its identity. Such calls for the return of the refugees in light of the return of control of most of Syria to the Syrian regime have been voiced several times by elements in the Lebanese political system.

International aid for treating refugees in Lebanon has declined, and the gap in funding has increased, placing a further burden on the already economically bleeding Lebanon. The number of refugees who voluntarily returned to Syria is low, as is the number of refugees who were sent back. The Lebanese state is exerting pressure to return Syrian refugees to Syria. In June 2022, Prime Minister Najib Mikati issued a statement calling the international community to help return the refugees burdening Lebanon back to Syria.

In July and August 2022, in light of calls and decisions in the Lebanese political system for the return of Syrian refugees, the Syrian National Coalition, an opposition body to the Syrian regime, issued a statement condemning the Lebanese intention to “send refugees to their deaths in Syria.”

Of course, the claim that all of Lebanon’s problems are caused by the Syrian refugees in its territory is incorrect. There is no doubt that the Syrian refugees in Lebanon are a burden on society, economy, infrastructure, and public services such as medicine, sanitation, and education. It’s a heavy burden. Undoubtedly, the ratio of one refugee to every four citizens is problematic, to say the least. However, the refugees are not to blame for Lebanon’s situation.

At this stage, there is no apparent solution for the Syrian refugees in Lebanon, and it seems that apart from statements and declarations, nothing tangible has been done in the matter. Even if Lebanon decides to expel them by force, it will be impossible to implement the actual expulsion of some 1.5 million people.

In our assessment, Syrian refugees will continue to be a cheap and exploited labor force throughout Lebanon, suffer harassment as a scapegoat, and continue to be a human reservoir exploited for terrorist purposes by all organizations outside and inside Lebanon. Nevertheless, the Syrian refugees will prefer to stay in Lebanon since they have no other reasonable alternative.