This month, we mark 17 years since the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1701, which led to the end of the Second Lebanon War.

The resolution “calls upon Israel and Lebanon to support […] arrangements to prevent the resumption of hostilities, including the establishment between the Blue Line and the Litani river of an area free of any armed personnel, assets and weapons other than those of the Government of Lebanon and of UNIFIL as authorized in paragraph 11, deployed in this area;”

The UN also demands the “full implementation […] of resolutions 1559 (2004) [..] that require the disarmament of all armed groups in Lebanon, so that […] there will be no weapons or authority in Lebanon other than that of the Lebanese State.”

The question of who is responsible for the mission of enforcing the resolution remains open since the formulation can be interpreted in different ways.

At the beginning, it states that UNIFIL must:

“Assist the Lebanese armed forces in taking steps towards the establishment of the area as referred to in paragraph 8 [between the Blue Line and the Litani River].”

In other words, this paragraph states that UNIFIL should not act alone to enforce the resolution.

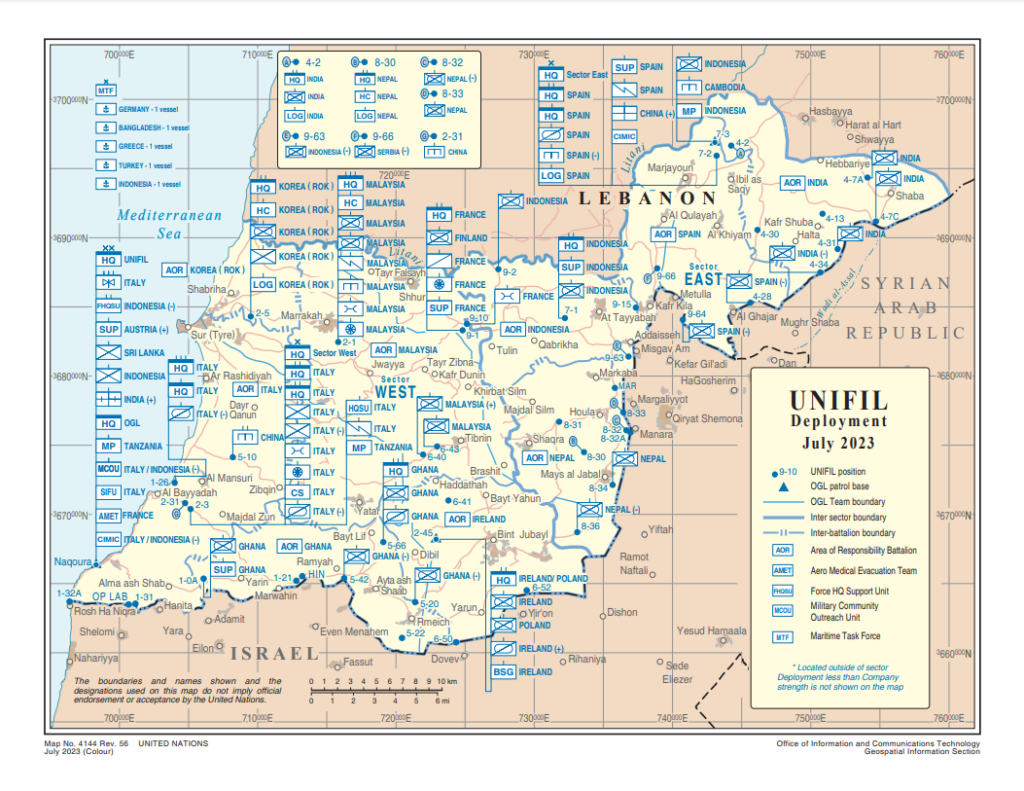

As a result, the UNIFIL force grew from 2,500 soldiers to 10,000 deployed in southern Lebanon, including a naval continent and additional European battalions from Spain, France, and Italy, in addition to the Irish-Finnish battalion that was already there.

But in a different part of the Resolution, it is written that the UN Security Council “authorizes UNIFIL to take all necessary action in areas of deployment of its forces and as it deems within its capabilities, to ensure that its area of operations is not utilized for hostile activities of any kind, to resist attempts by forceful means to prevent it from discharging its duties under the mandate of the Security Council, and to protect United Nations personnel.”

This can lead to the conclusion that UNIFIL is responsible for enforcing the resolution and that it has a mandate to take steps against those who try to breach the resolution.

Over the years, the State of Israel has argued that the mandate for enforcing the decision was given to UNFIL, but the prevalent stance in the international community is that the responsibility is on the Lebanese state. As a result, UNIFIL’s job is to assist the Lebanese Armed Forces in enforcing the decision.

In practice, the resolution is not enforced, and Hezbollah has tens of thousands of rockets and thousands of military operatives in UNIFIL’s area of activities, in a manner that threatens the security of the border with Israel, the stability of the Lebanese state, and UNIFIL soldiers themselves.

At the end of the month, the mandate will be renewed, as it is every year during a UN Security Council meeting.

Will this be the year that the UN finally recognizes the dangerous reality on the ground and UNIFIL’s ineffectiveness in creating a new security reality on the Israeli–Lebanese borders?

To answer these questions, it is necessary to bring up a number of figures from the latest monitoring report that the UN Secretary-General submitted to the Security Council regarding the implementation of Resolution 1701, spanning the dates of February 21 to June 20.

The good news is that there is, finally, a paragraph in the report on Hezbollah and a condemnation of its activities.

Later on, in Clause 78 of the report’s summary, the Secretary-General states that he remains “seriously concerned about the presence of unauthorized weapons in the area between the Litani River and the Blue Line.”

He then adds that the lack of cooperation with the LAF and enforcement attempts by UNIFIL on these issues “is unacceptable.”

He defines Hezbollah’s positions as a danger and calls for the disarmament of illegal weapons in Lebanon in general, in line with Resolution 1559. But that’s the end of it.

UNIFIL claims that out of 6,000 patrols conducted in the air, on ground vehicles, and on foot carried out by the force during the report’s timeline, only 20 of them experienced a disruption to freedom of movement.

It is clear that there are areas that UNIFIL simply avoids going into, like the Green Without Borders positions along the border, which are in reality dozens of Hezbollah positions set up over the past two years.

The 21 pages of the report paint a deeply upsetting picture of the border’s challenging reality, where Hezbollah operatives regularly attack and harass UNIFIL and break UN resolutions. The report depicts tension between IDF soldiers and Hezbollah operatives on the ground, which has reached a peak since the end of the last war, and it does seem like UNIFIL has the desire or ability to decrease this tension.

Here are a few figures from the report about unusual incidents during the timeline in question, a mere four months:

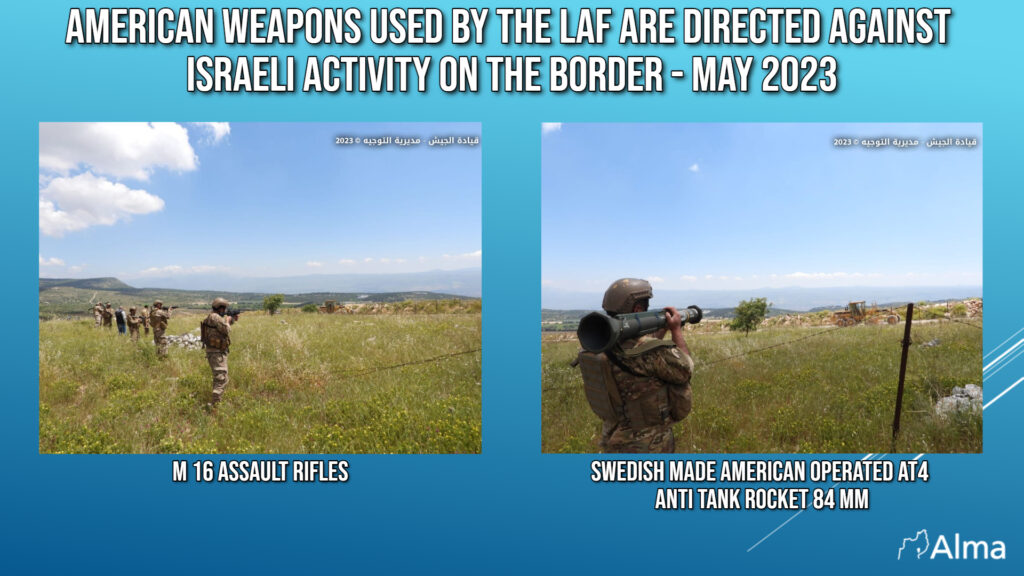

4 incidents in which LAF and IDF personnel pointed firearms at one another

“609 crossings south of the Blue Line by individuals in civilian clothing.”

This includes:

372 shepherds,

237 other

9 violations of the Blue Line by the LAF, usually for the purpose of “defusing tensions.”

11 Blue Line crossings by Israeli contractors building a security barrier

Four people were arrested by the IDF south of the Blue Line in three separate incidents. They were released by the Red Cross.

303 incidents of illegal or unauthorized weapons in the zone of operations, including hunting rifles (285 incidents).

21 incidents of illegal weapons, including:

Light machine guns, assault rifles, long-range rifles, and pistols

8 incidents in which weapons were identified were not for hunting at a range in the southern Lebanese town of Zibqin. Hezbollah flags were found in a range (finally, Hezbollah was mentioned in the report).

The report found 18 containers belonging to the Green Without Borders cover organizations, 6 towers (3 of which were near the containers), and out of the 18, only 12 had Green Without Borders signs.

19 vantage points that, we can assume, were designed for purposes such as overlooking a tunnel.

UNIFIL’s freedom of movement in these areas was restricted on a number of occasions, including the prevention of UNIFIL’s entry to a site near one of the containers. Some of these sites featured CCTV cameras.

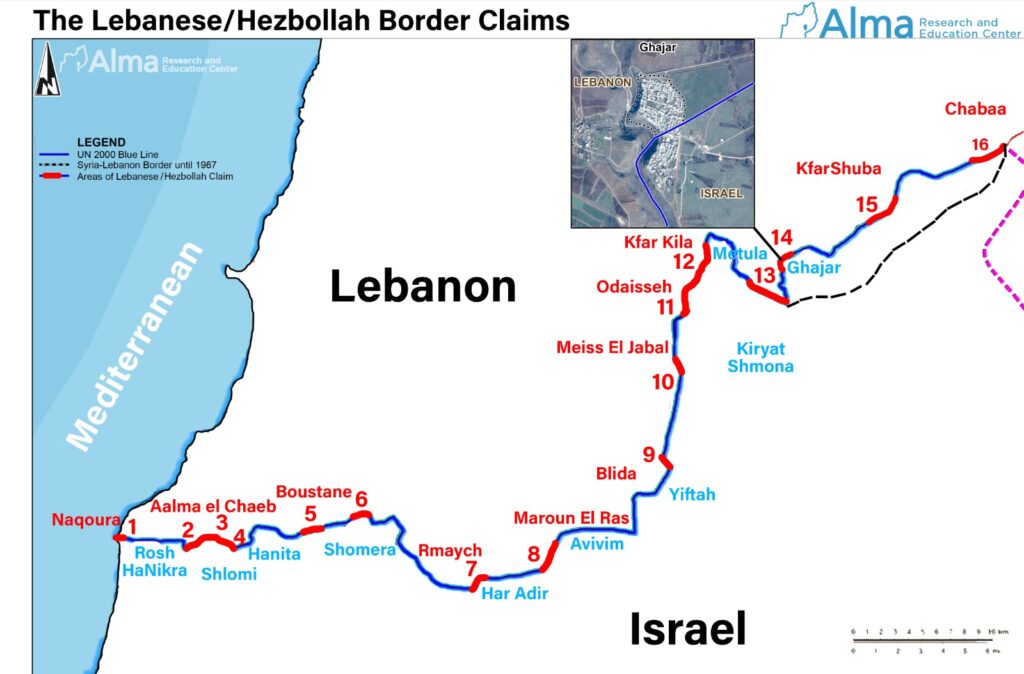

4 openings in the ground – 3 of them small – were found that could fit one person, as well as digging material on the ground, and one large opening was found at Alma el-Chaab in southern Lebanon.

In the summary, UNIFIL stresses that despite the repeated requests put to the LAF, UNIFIL did not receive full access to areas it is interested in, including Green Without Borders positions, the tunnels crossing the border, and four illegal ranges (meaning not belonging to the LAF).

The report also details a number of unusual and violent incidents:

March 7 – The theft of an ammunition magazine south of the Blue Line.

April 27 – The throwing of a smoke grenade in the Marwahin sector toward the IDF as it was busy with the building of the border barrier.

May 7 – A was tent identified by UNIFIL at Mount Dov south of the Blue Line. Individuals were spotted arriving at the tent, and CCTV cameras were installed. The report did not state who staffed the tent, despite clear footage delivered by the IDF.

The report notes that UNIFIL asked the LAF to dismantle the tents.

The report specifies in detail the training of Hezbollah out of UNIFIL’s area of activities. This is a violation of Resolution 1559, which calls for the disarmament of Hezbollah after the murder of the late Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri. An additional Hezbollah training event was held near the border with Israel right under a UNIFIL position, though this was not mentioned in the report.

It is clear from the figures that the situation is highly tense. In this regard it is worthwhile noting another 3 attacks against Israel, 2 from the period of the report and one after it:

First, the firing of 36 rockets from southern Lebanon on April 6. The incident is listed in detail in the UN report including a description of the Israeli response, which was limited. Secondly, the infiltration of a terrorist in the western sector with explosives and a suicide belt. The explosive device was planted at Megiddo Junction, some 70 kilometers from the border, and injured an Israeli driver. The terrorist was killed by Israeli security forces as he made his way back to Lebanon, a few kilometers from the border. The incident is not mentioned in the UN report, possibly because UNIFIL did not identify the infiltration.

An additional incident occurred on July 6, 2023, after the report was written, involving the firing of two anti-tank missiles, seemingly at an IDF patrol moving near the village of Ghajar, which fortunately ended without casualties.

In the past two years, we at the Alma Center have been assessing that Hezbollah has turned towards escalation and possibly even to war. Nasrallah is prepared to take more chances on the Blue Line to deliver achievements for Lebanon. This also occurred in 2022 regarding the maritime border, and we will know within months, it seems if there is natural gas on the Lebanese side.

Not long ago, Hezbollah’s leader delivered a clear threat regarding the land border as well.

First and foremost in Ghajar village, the northern part of which is classed as Lebanese territory. Nasrallah made it clear that Hezbollah would have a role in “solving the issue.”

The UN report calls on Israel to withdraw from northern Ghajar – a highly problematic humanitarian issue given that all villagers are Israeli citizens (more details on this further on).

At the same time, it calls on Syria to clarify its position on the Shebaa Farm – an area that Israel seized from the Syrians in 1967, but which the Lebanese claim to be theirs.

At the end of the month, the Security Council will vote, as it does every year, to renew UNIFIL’s mandate. The concern in Israel now is that the Lebanese are pushing to undermine the force’s independence.

Delegations from both sides visited New York and tried to influence the wording of the resolution.

In any case, from the data in the report itself, as well as its predecessors, it is clear that the force is not effective in implementing Resolution 1701. Even as a peacekeeping force, it failed to prevent attacks against Israel.

In wartime, the force’s soldiers will serve as a human shield

Therefore, as we have previously written, UNIFIL must be significantly reduced, In a way that maintains its ability for mediation and dialogue for tactical matters in the field – on these issues, the force has had a positive role and international involvement helped to reduce the flames in situations where neither side had an interest in escalation.

However, as mentioned, those days are over. Based on the very limited and moderate Israeli response to Hezbollah’s attacks and provocations and by Hezbollah’s Palestinian partners, it is clear that Israel is not interested in an escalation on the Lebanese border. This cannot be said for the other side.

In order to maintain dialogue and deal with tactical violations of the Blue Line, there is no need for an international force of 10,000 soldiers whose lives will be in danger during wartime, and the IDF will have to devote resources towards protecting them. A few hundred are sufficient.

UNIFIL GO OUT OR GO SLIM!

*Main Photo: UNIFIL soldiers on the Lebanese border (Twitter UNIFIL)