By: Yaakov Lappin and Tal Beeri.

Executive Summary

Following the special report we published on October 28, 2025, on the situational overview of Hezbollah’s rehabilitation program in Lebanon, in which we noted that one of the significant components of rehabilitation is Hezbollah’s capability to locally manufacture weapons on Lebanese soil, this analysis will examine this strategic necessity while examining and comparing it to the Hamas paradigm and the shift in Iranian proliferation doctrine.

At the height of Operation Northern Arrows, in November 2024, the Air Force, guided by the Intelligence Directorate, attacked a critical target in Janta, in the Beqaa Valley region of Lebanon—Hezbollah’s central precision missile manufacturing site. Even before that, the area had been attacked by Israel multiple times (such as in July 2024).

Hezbollah has not abandoned its efforts to manufacture missiles on Lebanese soil.

On September 26, 2025, the IDF attacked a site, again in the Janta area, for manufacturing precision missiles (likely the same site).

This attack is one of four strikes on the area since the November 27, 2024 Lebanon ceasefire went into effect.

Beyond the fact that these strikes confirm that Hezbollah continues to try to establish a domestic arms manufacturing infrastructure in Lebanon, the broader question is whether Hezbollah is relying more heavily on localized manufacturing than before the war, as a result of a significant blow to its weapons smuggling capabilities?

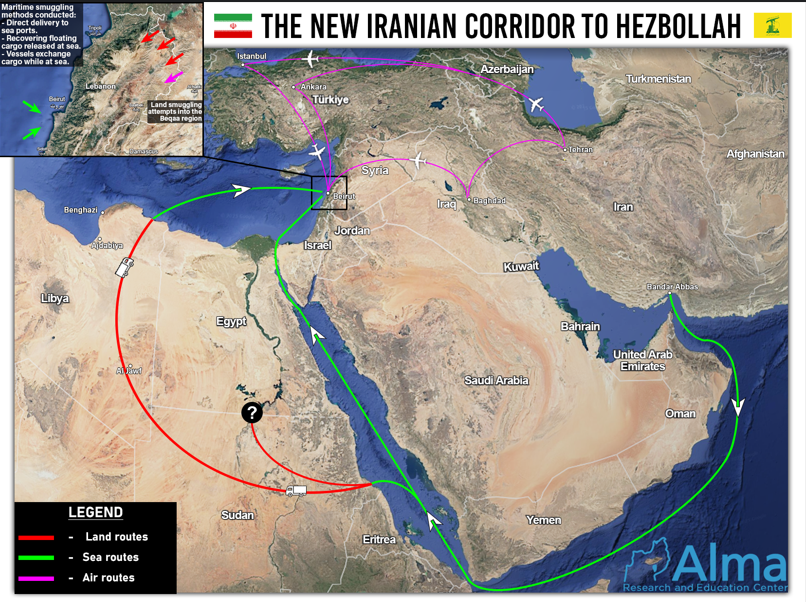

With the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024, Hezbollah lost a significant part of its smuggling corridor from Iran, whether via land convoys from Iran through Iraq and then to Syria and Lebanon, or via aerial smuggling through Syrian airports.

In Lebanon itself, the new government has also banned Iranian aircraft from landing at Beirut’s Hariri International Airport—blocking another direct supply route.

Despite this, concurrently, the Alma Center has regularly published and continues to publish on Hezbollah’s attempts to continue smuggling by land through Syria, and on the attempts and potential to establish alternative supply routes, likely mainly maritime, which are subject to Israeli interdiction efforts.

This new reality has transformed the domestic manufacturing of weaponry from a complementary need for the organization’s capabilities into an existential strategic necessity for continued force buildup, in a way that partially recalls Hamas’s transition in the Gaza Strip to a local arms manufacturing industry with Iranian support, after smuggling became more difficult to carry out via the Philadelphi Corridor (but nonetheless continued).

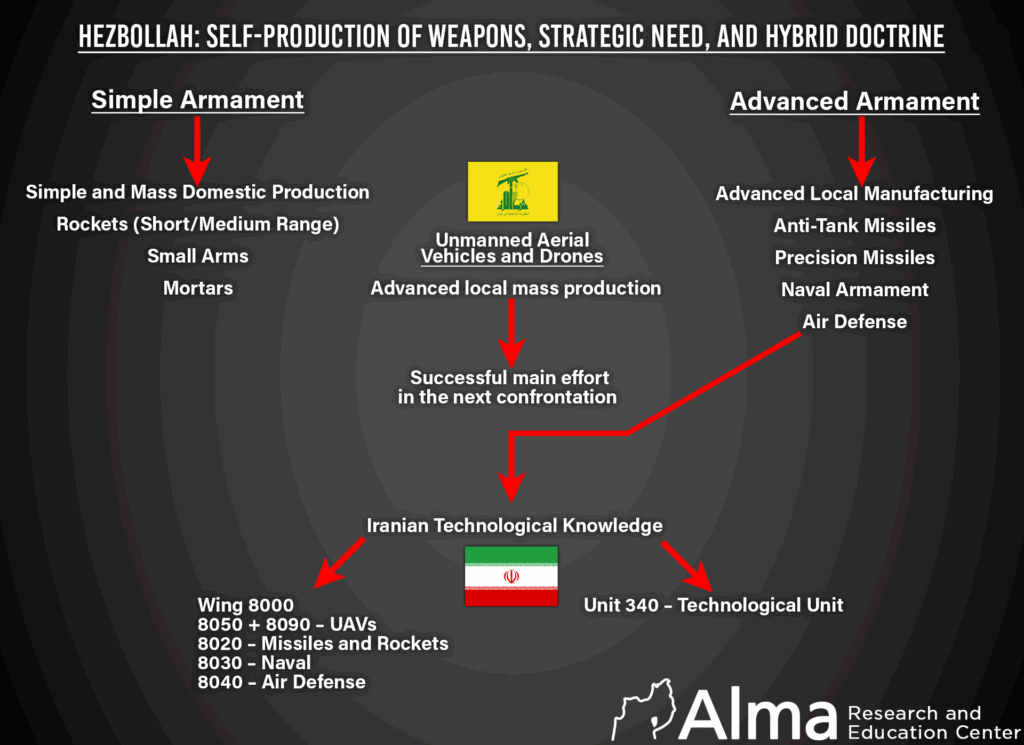

In our assessment, Hezbollah is developing a hybrid military-industrial strategy that combines the principles of local manufacturing demonstrated by Hamas, but adds efforts to produce advanced and precise high-end capabilities (precision missiles, advanced UAVs, and anti-tank missiles), supported by advanced Iranian technological knowledge.

Although these efforts are not new, we assess that given its regionally isolated situation, Hezbollah will turn to local arms manufacturing on a scale not seen before.

The end of the Corridor? A New Strategic Reality for Hezbollah

To understand the strategic urgency driving Hezbollah toward an industrial expansion for local arms manufacturing, one must first recognize the fundamental change in its regional map.

The collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian regime in December 2024 constituted a major strategic blow to the Iranian-Shiite axis.

This event disintegrated overnight large parts of the supply corridor that served as a main artery for transferring advanced weaponry, funding, and strategic depth from Iran to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

For years, Syria under Assad’s rule provided Hezbollah and Iran not only with a relatively safe transit route but also a rear base for operations, advanced weapons storage, and training.

The rise of the al-Sharaa regime in Damascus, with its Sunni orientation and clear interest in attracting reconstruction investments from Gulf states and the West, has turned Syria from a supportive environment into a hostile transit territory for the Shiite axis.

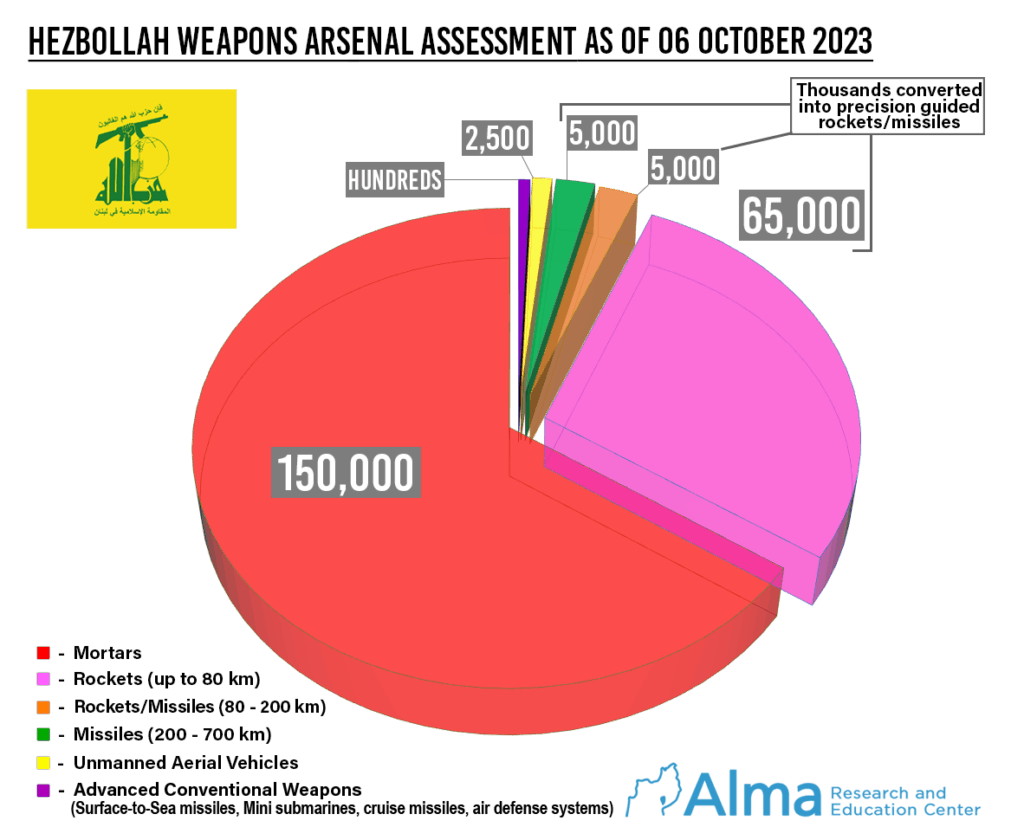

Until the fall of Assad, consistent Israeli military activity challenged the smuggling routes, but not in a way that substantially harmed Hezbollah’s force buildup, as evidenced by the scale of the organization’s arsenal on the eve of the Iron Swords War.

Hezbollah lost a state ally in Damascus that effectively connected the production lines of weaponry, whether in Iran itself or in Syria, to Hezbollah’s depots (in Syria and Lebanon).

Concurrently, pressure has increased in recent months on Lebanon’s official points of entry.

Beirut’s international airport and the seaports have become targets for heightened Lebanese oversight, and even the Lebanese government, under internal and external pressure, has increased (albeit in a limited manner) its efforts to prevent smuggling.

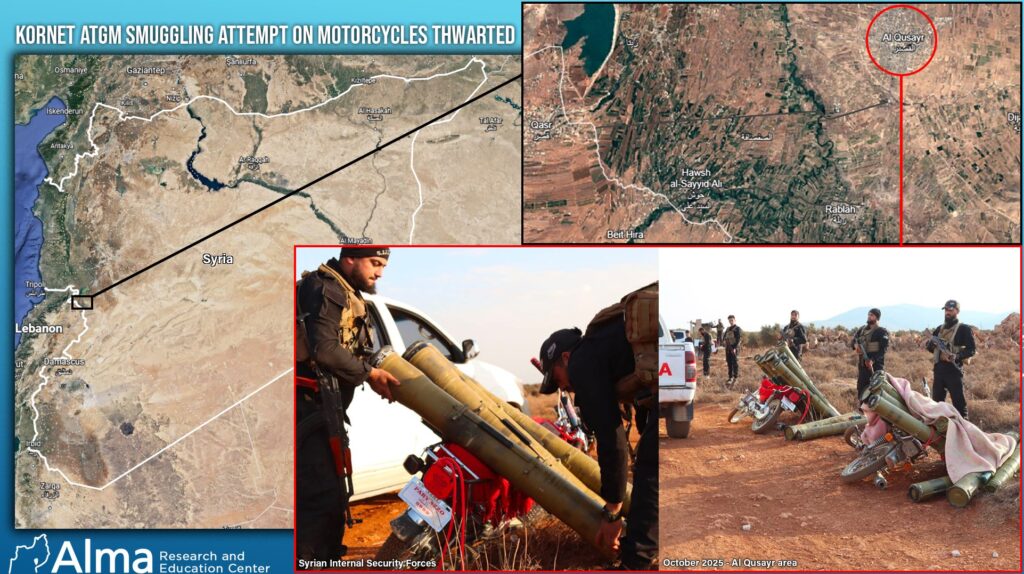

To this, one can add the actions of the new regime’s Syrian security forces, which report weekly that they have succeeded in thwarting smuggling from Syria to Lebanon, mainly in the al-Qusayr area (southwest of Homs / Lebanon’s northeastern border region).

This multi-domain pressure has made all supply routes—land, air, and sea—dangerous and unpredictable for the transfer of large, complete weapons systems.

The convergence of these factors—a land corridor that has significantly (but not completely) collapsed, a new hostile transit state in Syria that regularly acts to intercept smuggling efforts to Hezbollah, and the ongoing disruption of alternative routes—has turned Hezbollah’s dependence on external supply from a strategic advantage into a critical vulnerability.

The necessary conclusion for the organization’s leadership is that its force buildup concept in the current era can no longer be based on vulnerable external logistics.

Hence the clear strategic need: shifting the center of gravity from smuggling to manufacturing.

The new situation requires Hezbollah to ‘bring the factory home’ to Lebanon, and the understanding that the ability to locally produce weapons is the primary guarantee for its future as a significant military force and as an Iranian proxy.

It is important to note that this is a process that the Iranians and Hezbollah sought to achieve many years ago, and subsequently, we saw a growing trend of transferring production from Iran to Syria and from there to Lebanese soil.

However, as stated above, today this has become an essential and strategic necessity for Hezbollah.

The Hamas Paradigm: A Case Study in Local Military Industry

The model developed by Hamas in the Gaza Strip constitutes a unique case study of a local military industry (with self-sustaining capabilities), which developed and was refined under conditions of an Israeli security blockade, and provides fundamental lessons in resilience and adaptation.

Hamas’s military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, succeeded in reaching an advanced level of industrial independence, despite the ongoing security blockade on the Strip.

Hamas established a network of local workshops and factories, many of them underground, capable of producing a variety of weapons.

Hamas developed a systematic capability to convert dual-use materials, ostensibly civilian, for military needs.

A prominent example is the use of steel water pipes to produce rocket bodies, and simple chemical compounds, such as sugar and potassium nitrate (a common fertilizer), used to create solid rocket fuel.

The Gazan arms industry was built with Iranian funding and guidance. In effect, Hamas’s armament program was built out of the civilian economy.

A critical component of the model is the systematic process of collecting and dismantling unexploded Israeli ordnance, a process occurring as of this writing in the areas of the Strip under Hamas control (which currently controls 47% of the Strip’s territory).

According to estimates, between 10% and 15% of the ammunition fired by the IDF does not detonate. Hamas established and developed skilled technical teams to locate, collect, and safely dismantle these duds, thereby extracting high-quality military explosives and various components.

Gaza’s extensive tunnel network, the ‘Gaza Metro,’ functions not only as a military asset but also as a dispersed, concealed, and resilient industrial base.

These tunnels house workshops for weapons production and assembly, secure storage depots, and command centers.

This demonstrates the principle of embedding industrial capability within a subterranean and decentralized infrastructure, making its complete destruction a very difficult and lengthy task (according to an assessment by Defense Minister Israel Katz on October 26, 2025, about 60% of the tunnel system in the Gaza Strip has still not been destroyed).

Decentralization is not just an industrial tactic, but an entire doctrine. Similar to Hamas’s decentralized command doctrine, its production base is also not concentrated in a single large factory but is scattered in a network of small, hidden workshops.

The system’s resilience stems from the fact that destroying one workshop does not neutralize the overall production capability.

Although Hezbollah is at the top of the Iranian proxy food chain, it can look toward the Gaza Strip and draw relevant lessons for itself in the aspects described above in the context of rehabilitating and building its production infrastructure in a way that will allow it to withstand a future, sustained Israeli air campaign.

The Iranian Proliferation Doctrine: From Arms Supplier to Knowledge Broker

Hezbollah’s transition to self-production would not be possible without a parallel strategic shift in Iran’s doctrine of support for its proxies.

It appears that Tehran has gradually shifted over the years from being solely a primary supplier of complete weapons systems to a more sophisticated role of a broker of military-industrial knowledge.

This shift is the fundamental enabler of the indigenous production model, for both Hamas and Hezbollah.

The evolution of the Iranian support model can be traced. Support was characterized by the direct transfer of ready-made weapons systems, between 2013 and 2015, via Syria to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Most of these smuggling attempts were thwarted. In 2016, Iran and Hezbollah began a project to convert existing rockets in Hezbollah’s depots in Lebanon into precision missiles.

As part of this plan, Iran produced unguided rockets at a site in the SERS complex in northwestern Syria, and smuggled precision components separately to Lebanon, where technical teams converted the rockets into precision weapons at sites across Lebanon, including in Beirut.

When this program also failed to yield the results hoped for in Tehran and the Dahieh, from 2019, Iran and Hezbollah launched an ambitious program to manufacture precision missiles on Lebanese soil, including production and precision-conversion sites.

These sites produced missile engines, fins, navigation and control systems, and warheads.

Already in September 2019, the IDF exposed a site for precision missile manufacturing in the municipality of Nabi Chit in the Beqaa region.

The Iranian Revolutionary Guards played a critical role in transferring knowledge for these efforts through its technological units, such as Unit 340 for example, and Division 8000.

The shift in Iranian doctrine began even before the war, and therefore there is a critical need to monitor and disrupt these efforts in the post-war era.

Not only does local manufacturing help Hezbollah reduce exposure and disruption points in its force buildup process, assuming sites are not discovered, it also blurs Iranian fingerprints and allows it to maintain deniability.

This approach also significantly reduces the cost and logistical complexity for Iran of supporting its network of proxies.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and quadcopters: The Swarm Threat

Hezbollah’s dedicated aerial unit, Unit 127, is responsible for the development, production, and assembly of the organization’s diverse UAV array.

Israeli strikes on Unit 127 facilities in the Dahieh neighborhood of Beirut and in southern Lebanon, in the Nabatieh area, reportedly exposed production and storage sites for hundreds and even thousands of UAVs on Lebanese soil.

Hezbollah’s strategic aspiration, learned from the ‘Russian model’ in Ukraine, is to move from tactical strikes by individual UAVs to launching “swarms” in large quantities, designed to engage and overwhelm Israel’s air defense systems.

Hezbollah will seek to rehabilitate this serial production capability on Lebanese soil and turn the UAV and quadcopter effort into a major successful effort in the next campaign against Israel.

The capability to produce anti-tank missile systems on Lebanese soil is unclear at this time.

During Operation ‘With the Lions’, the Air Force attacked a site in Iran for manufacturing anti-tank missiles intended for Hezbollah, and it was reported that hundreds of anti-tank launchers were smuggled to Hezbollah from Iran.

In the same operation, the IDF attacked factories in the Tehran area that produced missiles, missile engines, and navigation components for missiles, from which the products were sent to Hezbollah in the preceding years.

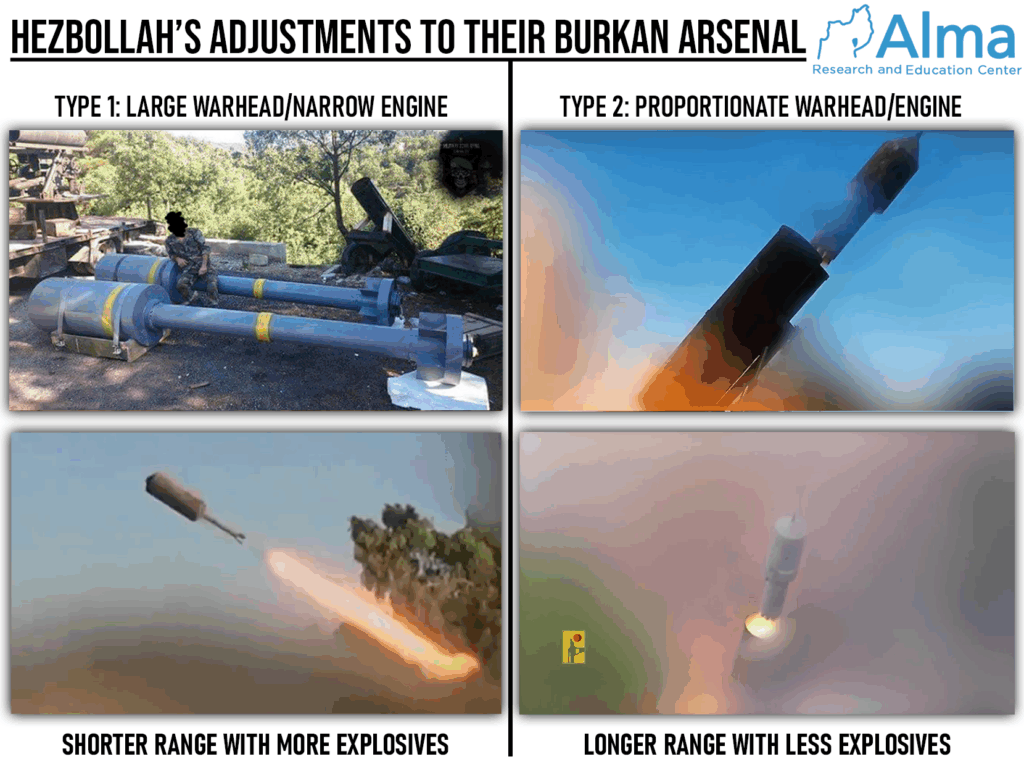

Parallel to its technological aspirations, Hezbollah may adopt the lesson from Hamas regarding the mass production of simple rockets and heavy mortar bombs (as Hezbollah began to do with the “Burkan” rocket, which it used frequently during the last war).

These means, although less sophisticated, are essential for creating continuous and large-scale statistical fire against troop concentrations and civilian communities near the border.

The lessons from Hamas regarding the use of available materials are particularly applicable in this category, and may push Hezbollah to try to build a deep ‘magazine’ of ammunition for a prolonged conflict.

Summary: The Rise of a Hybrid Threat

The future threat posed by Hezbollah is a dangerous synthesis of two models.

In our assessment, on the one hand, the organization will strive to adopt the resilience, decentralization, and ability to produce large quantities of simple munitions, as demonstrated by Hamas.

On the other hand, it will continue to develop and try to produce strategic and precision-guided weapons systems capable of threatening the critical infrastructure of the State of Israel.

This hybrid military-industrial doctrine may occur in the Lebanese underground, which already includes strategic internal smuggling tunnels, hardened much more than the tunnels in Gaza.

Israel, of course, is preparing for the continuation of the conflict with Hezbollah defensively and offensively, on scales that require analysis in a separate article.

But at this stage, the immediate question is whether the daily strikes in Lebanon are damaging most of Hezbollah’s efforts to build a domestic production infrastructure?

3 Responses

As always, very informative!

Dear Yaakov and Tal,

Your timely reporting and analysis reveal that the ayatollah regime and hezbollah are still continuing there decades long war by every possible means available to them. They are like a terminal cancer that must be totally eradicated for the recovery of both Lebanon and Israel. A comprehensive joint offensive by Israel and Lebanon is needed. The ayatollah, the IRGC, and hezbollah must be totally removed before recovery to legitimate governmental health can begin for both countries. There can be no peace with radical jihaddist terrorists until they are dead or gone from both countries. A cancer patient cannot be declared to be cured with a cancer still growing within. No hezbollah, no hamas, no abbas can remain. Please remove the cancer on both sides of the border, and remove the head of the snake in Iran (with its cancerous venom) so healing can begin.

Dear Yaakov and Tal,

If I may broaden the scope to a global scale, the same diagnosis and recovery plan is also applicable. In Europe and the USA the same islamo-nazi-marxist snake venom is causing societal delirium in both hemispheres and throughout the world. This is also a war of Truth vs lies, Light vs darkness, Good vs evil. From New York to London to Sydney to Moscow to every major city in the world this war is now being waged. All the nations of the earth are being shaken. The God of Israel will now execute Judgement and Justice throughout the Earth.