Executive Summary

One year after the rise to power of the new Syrian regime led by Ahmad al-Sharaa, a complex and deeply inconsistent picture is emerging: impressive diplomatic and economic achievements on the international stage alongside persistent, deep-rooted failures on the domestic front, including political, security, and social aspects. The gap between the narrative of a “New Syria” and the reality in the country is not accidental, but rather the result of a process in which international legitimacy preceded the construction of genuine governance.

On the one hand, al-Sharaa succeeded in breaking Syria’s isolation: most sanctions were lifted, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and its leaders were removed from terrorist designation lists, commitments for investments totaling tens of billions of dollars were secured, and the regime gained trust and support from Western and regional states. On the other hand, these achievements have scarcely translated into improvements in the population’s living conditions. The economy remains fragile, poverty and unemployment are extreme, civilian infrastructure is dysfunctional, and most refugees are unable or unwilling to return to the country.

On the domestic front, there is a clear ongoing failure to lay the foundations for a representative and inclusive state. The parliamentary election process was electoral in form only, lacking genuine civic participation, and failing to provide adequate representation for minorities or women. Decision-making remains centralized and opaque, with power concentrated in a narrow circle around the president. At the same time, rule-of-law institutions are being weakened through the creation of extra-legal mechanisms that undermine judicial independence.

The most serious challenge lies in internal security and the protection of minorities. The violent incidents and massacres against Alawites and Druze during 2025, alongside daily violence against minority groups and women, expose a deep systemic failure. Even when no evidence was found of direct orders from the political leadership, the involvement of security personnel and the absence of effective control over them point to a structural problem: an army and security forces composed of rebranded militias, some of which adhere to extremist Salafi-jihadist ideology and whose loyalty to the regime is selective.

Alongside this, gradual Islamization is taking root within the education system, driven largely by HTS-affiliated institutions that have filled the void left by the collapse of public schooling. This development erodes the foundations for a shared civic identity and heightens anxiety among minority communities.

Regionally and internationally, Syria risks once again becoming an arena of influence for external actors, primarily Turkey and Russia, at the expense of its sovereignty and with increased instability. For Israel, the evolving reality in Syria constitutes a persistent security threat: multiple armed actors, the presence of terrorist organizations, stockpiles of advanced weapons in southern Syria, and growing involvement of foreign actors near the border.

The main conclusion is that the “New Syria” stands at a critical crossroads. Economic reconstruction without deep political, institutional, and security reforms is not a recipe for stability, but rather a postponement of the next crisis. The international community, which chose to invest in al-Sharaa due to the absence of alternatives, must set conditions, oversight mechanisms, and a clear roadmap toward rule of law, pluralism, and minority protection. Israel, for its part, must pursue a cautious, gradual, and sober policy: combining freedom of action with willingness to reach security arrangements, yet without illusions regarding the current regime’s ability to deliver genuine stability and enforcing law and order at this stage.

Introduction

On December 8, 2025, Syria marked one year since the rise to power of the new regime, led by “interim” President Ahmad al-Sharaa. Since taking power, the new regime has faced a difficult challenge: rebuilding a shattered state after more than a decade of civil war and nearly five decades of brutal and corrupt dictatorial rule. Syria is currently in a complex transitional period, characterized by persistent instability and deep uncertainty regarding its political, security, and social future.

The rise of the new regime was accompanied by a wave of hopes and promises for a “New Syria”, united, stable, with a representative political system based on equal rights for all citizens. Over the past year, the new regime has initiated reforms, mainly in economic and institutional fields, as well as renewed diplomatic relations with regional and Western countries, steps seen as essential to national reconstruction.

A review of the developments that took place in the past year points to certain achievements, particularly in the economic sphere and international relations. However, other areas, especially domestically, reveal a more troubling picture. There are centers within the regime and its various arms staffed by individuals with an Islamist-extremist, jihadist background and worldview, particularly in the army and security forces; severe violence against minorities is evident; the regime struggles to establish effective control over the entire territory of Syria; and the political system remains centralized and is not representative of all minority groups in Syria..

Without solid political and institutional foundations and without implementing an inclusive and pluralistic governing system, the new regime will struggle to translate the promises and expectations placed upon it by Syrian citizens and the international community into a reality. In the absence of a genuine alternative to the current regime, failure to stabilize the state will likely lead to Syria’s collapse and chaos, a return to civil war, or takeover by terrorist organizations and external actors. Such a scenario would pose a threat to Israel’s security and regional stability.

Syria on the International Stage – the “Charm Offensive’

Upon taking power, al-Sharaa began working to renew diplomatic relations with regional states, the West, and the international community. During an intensive international public-relations campaign he met with leaders and representatives from numerous countries worldwide. The campaign aimed to present a moderate image: the new President and diplomat Ahmad al-Sharaa, rather than the terrorist and jihadist Abu Mohammad al-Julani.

The primary goals of al-Sharaa’s PR campaign were the removal of sanctions on Syria and securing economic aid and investments, moves essential for Syria’s reconstruction. Since according to World Bank estimates, the cost of rebuilding Syria ranges between USD 200–400 billion.

Al-Sharaa achieved significant diplomatic success. He managed to secure the removal of most sanctions on Syria by the United States and the UN and the delisting of HTS, including himself and his associates, from the terrorist lists of the US, UK, Canada, and the UN. On 18 December, the United States unconditionally lifted the most significant sanctions imposed on Syria during the Assad regime, known as the “Caesar Act.” Al-Sharaa also secured economic, logistical, and technological investments and partnerships worth billions of dollars (details below) and established diplomatic relations with numerous countries. Al-Sharaa gained legitimacy, support, and goodwill from the international community and succeeded in erasing his problematic past from international memory (see our article published December 8).

The West places its hopes for a stable, secure Syria with a Western orientation in al-Sharaa. The absence of an alternative regime places him in a position of strength to demand aid and support to prevent Syria’s descent back into chaos. Al-Sharaa adopts a highly pragmatic approach, ready to engage with any country or partner willing to assist Syria, even former enemies such as Russia (he even stated he does not rule out renewing ties with Iran).

Al-Sharaa’s diplomatic strategy may lead to two outcomes. The first is Syria becoming a playground for external powers such as Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, or Russia, this is a likely scenario if the regime is too weak and the support becomes interference in Syria’s internal affairs. The second outcome is that al-Sharaa capitalizes on the current situation, with numerous actors wanting a role in building the new Syria, and growing international rivalries, to extract benefits from all sides without any commitments, thereby consolidating his rule and gaining regional and international influence (similar to Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s diplomacy in the 1950s, leveraging US-Soviet rivalry).

Despite diplomatic success thus far, it has not translated into meaningful improvements in living conditions. According to a December 2025 UN report, since the fall of the Assad regime, 1,208,000 refugees have returned, mostly from neighboring countries (Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt). Only 1,900 returned from EU countries. In addition, Syria currently has approximately 7.4 million internally displaced persons. More than two million people displaced inside the country have gone back to their areas of origin, however many are coming back to damaged or destroyed homes, with limited access to electricity, water, healthcare or jobs and remain dependent on humanitarian aid.

Over 6 million Syrian refugees remain abroad. While EU states hope for rapid refugee returns is driving their strong support for the new Syrian regime, the reality is that Syria currently lacks the capacity to absorb such numbers. Ninety percent of citizens live in poverty, 65% are unemployed, only 37% of the healthcare system functions, and only 65% of schools operate. Infrastructure conditions further prevent refugee returns. Reconstruction has not yet begun and currently appears driven by private initiatives rather than the state. Many refugees, already integrated elsewhere, fear returning, concerned by unstable security conditions.

Democracy on Paper

After taking power, al-Sharaa pledged to build a representative political system, accountable and transparent state institutions, end the corruption of the Assad era, and draft a constitution guaranteeing the rights of all Syrian citizens. One year later, the gap between promises and reality remains significant, to say the least.

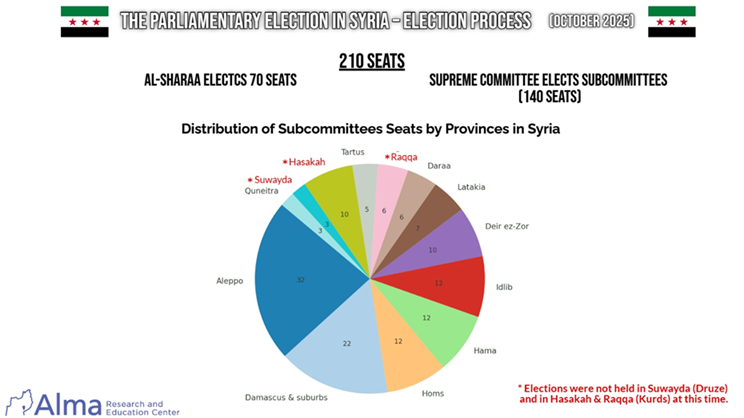

In early October 2025, Syria held parliamentary elections (People’s Council), the first since the fall of Assad and a key test for Syria’s political process. The elected council faces crucial tasks shaping Syria’s future, including drafting a permanent constitution, economic reforms, and strengthening state institutions. However, instead of general and direct elections, an electoral-college system was used.

The Supreme Elections Committee, appointed by al-Sharaa, determined seat allocation and appointed sub-committees. These sub-committees selected representatives from among 1,570 candidates. Out of 210 seats, two-thirds were selected by the sub-committees, while one-third were to be appointed by al-Sharaa, who, at the time of writing this article had not announced his selections nor explained the delay.

The implication of this model is that Syrian citizens did not vote. According to regime officials, current conditions do not allow direct elections. They argue that holding elections, even limited ones, strengthens democratic development. In minority regions such as Suwayda (Druze), Hasakah, and Raqqa, elections were not held because “the environment is unsafe” and the government lacks full control.

The election results failed to represent minorities or women. Of 119 elected seats, only six went to women and ten to ethnic minorities. The elections were largely symbolic and “marketing-oriented,” creating the appearance of democracy without genuine participation.

Moreover, decision-making remains centralized. According to a December 2025 Washington Institute report, most major decisions are made within the Foreign Ministry’s General Secretariat for Political Affairs (GSPA) under Foreign Minister Asad al-Shaibani. This body functions effectively as a shadow government which undermines transparency and responsiveness of government institutions.

The involvement of al-Sharaa’s associates and family in key government roles raises further concerns. While al-Sharaa seeks to avoid perceptions of corruption, warning officials not to replicate Assad-era practices. He also issued a statement in the Syrian media calling on regime officials to report their investments and not take on new projects and even shut down one brother’s business. Reports indicate that bribery remains widespread, particularly to avoid detention, release prisoners, or recover confiscated property. Reuters reported settlement deals with individuals linked to the Assad regime involving asset transfers in exchange for permission to resume work in Syria. A committee on illicit gains was established, yet some members are reportedly under investigation themselves for suspected wrongdoing.

Recently, the human-rights organization “Syrians for Truth and Justice” addressed the creation of the role of Head of Judicial Directorate, also known as the “Sheikh”, a new position allegedly above the Attorney General and court presidents, despite lacking a legal basis. Created by a decision of the Ministry of Justice, it requires no legal education or experience and holds authority over judicial promotions, transfers, salaries, leave, and dismissals, which potentially undermines judicial independence through an illegal parallel structure.

This raises questions about the depth and authenticity of institutional reforms. Are they sufficient? Likely not. Without international guidance and support, democracy is unlikely to take root in Syria. The international community must take an active role in the state building process in Syria to insure its transition to a stable and secure state (See article published on November 11, 2025).

Domestic Security: Law Without Order

One of the regime’s most complex challenges is internal security and maintaining order, particularly regarding minority protection. Tensions between minority groups and between minorities and the regime threaten stability and hinder national unification.

Over the past year, two major massacres occurred. The first, in March 2025, targeted the Alawite minority in coastal and western Syria. A UN report (August 2025) identified it as a massacre involving killings (including women and children), torture, corpse desecration, looting, and destruction of property. The report documented gross violations of human rights across 16 locations including Latakia, Tartus, Homs, and Hama. Approximately 1,400 were killed and tens of thousands displaced. While no evidence showed direct government orders, Syrian security forces participated, indicating lack of control over forces particularly those with jihadist backgrounds.

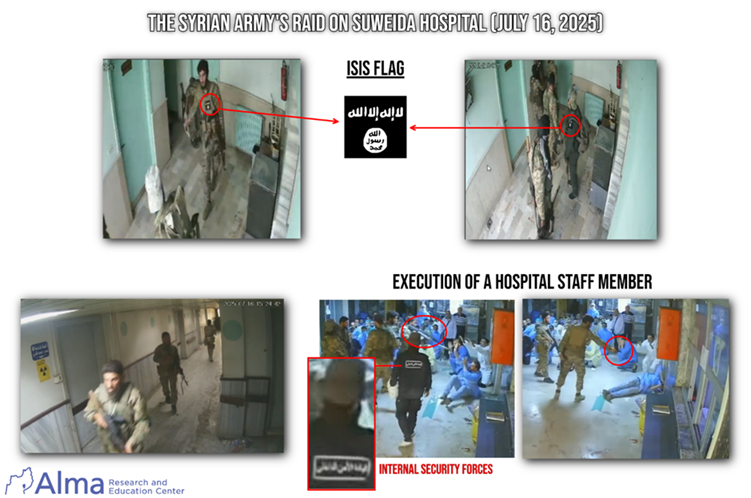

The second incident occurred in July 2025 in Suwayda District, the Druze heartland (about 750,000 people). Clashes between Bedouins and Druze escalated into violent intervention by the army and security forces. A UN report documented over 1,500 deaths (including women and children), nearly 200,000 displaced, kidnappings (at least 105 Druze women abducted), looting, destruction, and sexual violence against women and girls. Videos and testimonies show security forces participating, including executions of civilians (see article published July 17).

In the wake of these events, the regime established investigative committees to examine the incidents described above, both in the Alawite area and in the Druze area, in order to identify those responsible and bring them to justice. Authorities claimed the March violence followed a local uprising. Investigators acknowledged security force involvement but found no command-level orders. They denied kidnappings of women or girls, contradicting UN findings.

According to human rights organizations, the committee did not provide information on whether the investigation also examined the role played by senior military or regime officials in the events. According to reports by human rights watch in Syria, while no direct order was issued by the regime to carry out the massacres, the Syrian Ministry of Defense played a central role in mobilizing units and coordinating their deployment.

The authorities mobilized tens of thousands of fighters from across the country and assigned them to joint areas of operation. Fighters reported receiving instructions through channels linked to the Ministry of Defense, including orders to transfer responsibility for areas they had “secured” to the General Security forces.

In November 2025, the first trial began against those accused of involvement in the violence against the Alawites. The public prosecutor filed indictments against approximately 300 individuals linked to armed factions affiliated with the army who participated in attacks on Alawite communities, and against around 265 individuals who belonged to semi-military groups from the Assad era accused of taking part in attacks against government forces.

An internal investigation committee was also established to examine the events in Suwayda. In November, it was reported that Syrian authorities had arrested several security personnel who were involved in the clashes in Suwayda and could be identified through footage from the events. Syrian citizens, particularly from Suwayda, have cast doubt on the credibility of the internal investigation, arguing that no effort has been made to examine the chain of command or determine who was responsible for the massacre. The investigation focuses on specific individuals, even though the killings were systematic and, according to their claims, directed from above. Citizens state that they place greater trust in the UN’s independent investigation.

Beyond these incidents, UN and human-rights reports document daily violence against minorities, Druze, Alawites, Christians, including assaults, shootings, kidnappings (especially women), threats, and property damage. In the first half of 2025 alone, dozens of women and girls were reportedly kidnapped and sexually assaulted. Authorities often dismiss reports as false; the Interior Minister claimed only one of 42 cases was found credible.

The result is deep mistrust among minorities regarding the regime’s ability or willingness to protect them. In August, 400 minority representatives convened, calling for a decentralized state and a new constitution guaranteeing pluralism. The government accused some participants of separatism.

Among Druze, Alawites, and Kurds, opposition to the new regime’s authority persists, alongside demands for autonomy driven by concerns for their rights under the new regime.

These cases point to a systemic failure to protect minorities and women in Syria. Moreover, they also highlight the regime’s lack of control over its security forces, some of whom hold extremist Islamist ideology and beliefs, leading them to exhibit selective loyalty and obedience to the regime.

Reforms, Investments, and a Shadow Economy

After over a decade of civil war, systemic corruption, isolation, and sanctions, Syria’s economy is essentially bankrupt and requires comprehensive reforms. The new government is implementing major financial regulatory reforms aimed at reconstruction, economic recovery, and reintegration into the global financial system. This process is meant to modernize banking, attract foreign investment, and restore public trust.

For example, in November 2025 the Syrian banking system began the process of reconnecting to the global SWIFT network. The Central Bank of Syria (CBS) confirmed the successful completion of international transfers, which are essential for facilitating foreign trade, reducing transaction costs, and attracting foreign currency. Re-integration into the international financial system triggered a series of regulatory reforms aimed at meeting international standards and leveraging renewed access to global financing.

The reconstruction of Syria’s economy depends largely on the removal of the sanctions imposed during the Assad regime. The United States began the process of lifting sanctions on Syria in late May 2025. On December 18, 2025, the United States removed the stringent sanctions imposed on Syria under the “Caesar Act” (a process that began in November but required congressional approval). The European Union likewise lifted its economic sanctions on Syria. In addition, the United States, the United Nations, the United Kingdom, and Canada removed HTS, al-Sharaa, and his interior minister from their lists of terrorist organizations and individuals, a step also intended to enable foreign investors and allied states to maintain unrestricted economic ties with Syria.

Foreign investments are indeed flowing into Syria. Syria has signed a memorandum of understanding with a consortium of international companies led by Qatar’s UCC Holding to develop large-scale power generation projects, with foreign investment estimated at approximately $ 7 billion. Saudi Arabia has committed $ 6.4 billion in investment. These investments will include projects in infrastructure, energy, finance, telecommunications, real estate, trade, and tourism. Also, under consideration are deals to develop Syria’s energy and electricity infrastructure with companies from the United Arab Emirates (Dana Gas), the United States (GE Vernova and Chevron), and Germany (Siemens Energy). While Syria is in clear need of investment and partnerships, the risk lies in excessive involvement by external actors in Syria’s internal affairs to advance their own regional interests.

The Governor of the Central Bank of Syria stated in early December 2025 that the Syrian economy was growing at a faster pace than World Bank estimates (1%). He also noted that Syria is working to establish regulations to prevent money laundering and the financing of terrorism and is cooperating with the IMF to collect economic data that accurately reflects this resurgence. The vision is for Syria to become a regional economic hub. In December 2025, the company Visa signed an agreement with Syria to develop a digital payment system.

Despite the advancement of reforms and economic deals, not all that glitters is gold. According to reports from March 2025, Syria received oil from Russian vessels subject to international sanctions, a move that could have undermined the process of lifting sanctions on Syria. Cooperation with sanctioned actors (including business figures linked to the Assad regime), the acceptance of bribes, lack of transparency, and the management of informal economic systems may damage the economic reforms Syria requires and erode the confidence of potential investors and allies such as the United States and European Union countries.

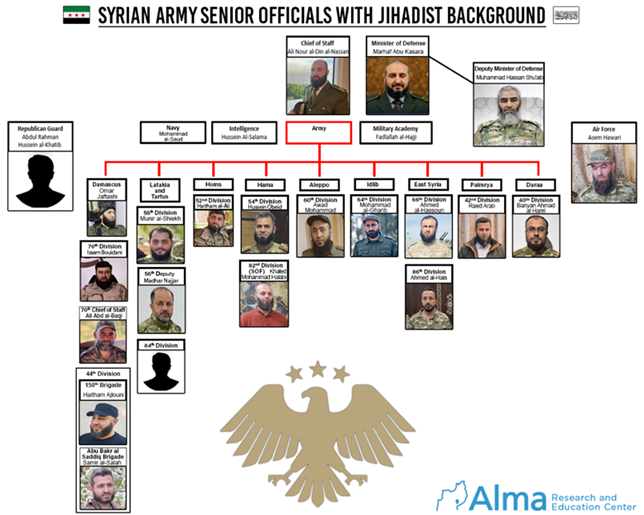

A New Army or Militias in Uniform?

Shortly after the takeover of Damascus in December 2024, the new Syrian regime began efforts to rehabilitate and rebuild the Syrian army. As early as January 2025, al-Sharaa’s associates called on the commanders of the various organizations and militias to submit to the regime, disarm, and integrate into the new army, and conducted negotiations with them through a series of talks (see the special report we published on August 5).

The new regime succeeded in rehabilitating a significant portion of the army’s command structure: it reestablished military frameworks, created new ones, and appointed key officials. In addition, the Ministry of Defense appears to be working to return officers who served in Assad’s army to active service, primarily in professional roles or positions requiring specific experience that could assist in rehabilitation and capacity-building.

Despite these rehabilitation efforts, this does not amount to the creation of a new, heterogeneous army built and designed from the ground-up. While many organizations that operated under HTS, the SNA, and others agreed to join the new army, numerous reports indicate that this was not a genuine dismantling of those organizations and militias, but rather their rebranding under divisions and brigades of the new Syrian army. In many cases, these organizations retained their existing structure, identity, and internal command. Moreover, in some instances, they continued to operate in the same areas in which they had previously been active. This is particularly true of forces operating in northern Syria under the SNA and with Turkish support.

Furthermore, a substantial portion of the fighters in the new Syrian army adhere to an extremist Salafi-jihadist orientation. Some are ideologically not far removed from ISIS, and some are even foreign fighters who have settled in the country. This ideology, aimed at imposing Sharia law and eliminating minorities, contradicts the “pragmatic” trends the regime seeks to “market” externally and raises serious concerns about Syria’s future internal stability. As noted, the regime does not exercise full control over the new security forces, and in the two violent incidents that occurred in Syria in March and July 2025, security personnel were found to have taken part in the massacres (apparently acting independently).

According to a recent article in the New York Times the new leadership in Syria prefers to integrate former fighters from HTS into the military over those who may have more expertise and experience. In addition, minorities are currently not able to enlist in the military which could lead to increase in sectarian tensions.

Despite efforts to integrate all militias in Syria under the Syrian security forces, the regime has so far failed to implement the agreement signed in March 2025 with the Kurdish SDF militia to unify their military and civilian institutions with the state. The agreement includes a complete cessation of hostilities, recognizes the Kurds as an integral part of the state, and guarantees the participation of all Syrian citizens in the political process. The main obstacle to implementation is the SDF’s demand that its forces be integrated as a single unit within the army, while the regime seeks to disperse them among different units. Another obstacle is the Kurdish demand for a decentralized political system.

The Kurdish forces were the United States’ principal allies in the fight against ISIS. The SDF controls approximately 46,000 square kilometres in northeastern Syria. Around 10,000 ISIS fighters are held in prisons managed by the SDF, and an additional 45,000 individuals linked to ISIS operatives (their families, mainly women and children) are held in several camps. The withdrawal of U.S. forces from Syria has raised Kurdish concerns about their future. Some Kurds have called for autonomy, but Syria and Turkey strongly oppose this. Turkey has even threatened that any Kurdish attempt at independence would provoke a military response. Despite attempts to implement the agreement, violent clashes between Kurdish forces and Syrian regime forces continue daily.

Ankara and Moscow Return to Damascus

The involvement of foreign actors, among them Turkey and Russia, in Syria’s security affairs once again raises concerns that Syria may become a tool serving external interests and a threat to regional actors, including Israel.

In August 2025, Syria signed a security agreement with Turkey. Under the agreement, Turkey will provide weapons, equipment, and logistical support. In addition, Turkey will train Syrian army forces and advise Syria on military and security matters. Turkey’s foreign minister warned Israel and the Kurds in Syria to refrain from actions that could undermine Syria’s stability. Israel carried out several strikes in Syria against Turkish entrenchment efforts, aiming to delineate boundaries and establish red lines on the ground (see the article we published in January 2, 2025)

Turkey’s involvement in Syria is not limited to security and military matters alone. Turkey is also deeply involved in civilian reconstruction, raising the central question of whether al-Sharaa’s regime is, in effect, intended to function as a Turkish proxy?

The Turkish “project” in Syria—cultivating the forces of Abu Mohammad al-Julani / Ahmad al-Sharaa, has been a multi-year endeavor that began with the entrenchment of his forces in the Idlib enclave and the establishment of the “Salvation Government” there, and reached its peak with the overthrow of the Assad regime with full Turkish backing.

The Turks are now seeking to “reap the fruits of their labor” …

Russia is also interested in preserving its presence and influence in Syria. In October 2025, al-Sharaa met with Putin in Moscow. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss the renewal and/or preservation of relations between the two countries. Prior to al-Sharaa’s visit, several Russian military and civilian delegations visited Syria. According to reports in the Arab media, the Syrians are interested in the deployment of a Russian military force in southern Syria, similar to the deployment that existed during the Assad era. The goal is to prevent Israel from striking in Syria. According to various reports, the Russians have also resumed patrols in northern Syria, where clashes have occurred between Syrian forces and Kurdish forces.

In November 2025, another senior Russian military delegation visited Syria. According to the official statement, the visit discussed ways to expand military cooperation and coordination mechanisms in the areas of training, knowledge and experience exchange, and continued implementation of military-technical agreements between the two sides. On November 20, it was reported that Russia had begun practical steps to restore and strengthen its presence in southern Syria, particularly in the Quneitra District near the Israeli border, by reestablishing nine military positions it had previously operated. According to the report, on November 17 a senior Russian delegation conducted a field tour in the Teloul al-Hamar area near the disengagement line, accompanied by officials from the Syrian Ministry of Defense, to examine the feasibility of returning to the area.

Needless to say, Russia seeks to maintain its presence at its air and naval bases in Hmeimim and Tartus (on the western coast) as well as its air force base in Qamishli (northeastern Syria), enabling it to preserve its influence in the region.

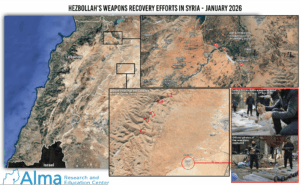

Israel in Syria: Old-New Threats

Since the fall of the Assad regime, Israel has been operating in the buffer zone along the Syrian border in order to thwart emerging security threats, including terrorist activity and the smuggling of weapons. Despite the political change in Damascus, Syria, particularly southern Syria, in areas adjacent to the Israeli border, continues to serve as an arena for the activity of various armed actors, including Iranian terror cells, Hezbollah, ISIS, Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, al-Jamaa al-Islamiyya, and other organizations. In recent months, there have also been reports of a renewed increase in ISIS activity across the country, especially in southern and eastern Syria, a trend that underscores the depth of the security challenge in the region.

The weapons seized over the past year in southern Syria by Syrian security forces point to a significant threat potential. For example, on December 10, Syrian security forces raided a weapons depot established on a farm in eastern Deraa District. The depot contained 42 Sagger anti-tank missiles and four Metis anti-tank missiles, along with their launchers. Over the past year, similar weapons seizures have taken place by Syrian security forces in southern Syria, though not on a scale or quantity that reflects the actual volume of weapons present in the area. Such weapons are intended, among other things, for potential use by local terrorist cells operated by the Shiite axis, ISIS, or Palestinian organizations against IDF forces operating in southern Syria, a scenario that could lead to broad security escalation. In addition, there is a real potential for these weapons being smuggled via Jordan into the West Bank, altering the security threat landscape there. Against this backdrop, direct talks between Israel and Syria have been taking place in recent months, mediated by the United States, with the aim of formulating a security arrangement. However, substantial gaps between the sides, including issues related to the withdrawal of IDF forces, the demilitarization of southern Syria, and the establishment of a humanitarian corridor in the Suwayda area, continue to delay the establishment of an agreement.

Israeli activity in Syria has led to a rise in hostility and resistance among the local population. For example, on 19 December 2025 it was reported that the town council of Khan Arnabeh issued a call for a protest demonstration/solidarity stand against “Israeli incursions” in the Quneitra area. Protest participants in Quneitra carried signs against the “raid policy” and against engineering work and excavations that, they claimed, damaged agricultural land and infrastructure and created an atmosphere of instability and intimidation among residents. These hostilities could escalate and pose a threat to Israeli forces in Syria.

Given the complex security environment, Israel should continue to seek an arrangement with Syria, but only with caution and a firm commitment to safeguarding its core security principles and national interests. Any agreement that overlooks the realities and threats on the ground risks exacerbating instability and undermining, rather than enhancing, the security of Israel’s northern border.

The Classroom as a Mosque: Syria’s Education System

On November 1, the Syrian Ministry of Education announced that approximately 40% of schools across the country are still destroyed because of fighting and bombardment over the past 14 years. According to UNICEF data, about 3 million Syrian children are outside the education system.

Filling the void created by the collapse of Syria’s public education system, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham’s education network, “Dar al-Wahi al-Sharif”, has moved in. Over the past year, the “Dar al-Wahi al-Sharif” schools have undergone a reform that integrates Islamic and Sharia studies and Qur’an memorization alongside scientific and practical disciplines.

The “Dar al-Wahi al-Sharif” (“House of the Sacred Revelation”) education system belonging to the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham organization, currently operates (as of December 2025) in over 70 schools and 28 kindergartens, which are no longer limited to Idlib but are expanding into the districts of Damascus, Homs, Aleppo, Daraa, Latakia and Hama. The “Dar al-Wahi al-Sharif” system is supported by the organization and receives external philanthropic assistance, while exploiting the education crisis in the country’s public schools (A more in-depth discussion of “Dar al-Wahi al-Sharif” will be presented in an upcoming article).

Another example of the entrenchment of Islamist narratives in Syria’s education system is morning assemblies with a jihadist character. In a video recently filmed at one of the schools in Syria, students are seen participating in a morning assembly, standing in rows and repeating in unison after a teacher who delivers religious statements of a clearly ideological/jihadist nature. Their exact translation is:

“Allah is our goal. The Prophet is our role model. The Qur’an is our constitution.

Jihad is our path. Dying for Allah is our highest aspiration.”

It is possible that we are witnessing a troubling process within Syria’s state education system, taking place under the new regime and with its guidance. This points to a process of Islamization in education in certain parts of the country—a process in which religious symbols, Qur’anic verses, and jihadist rhetoric replace secular, civic, or national messages.

Conclusion

One year after the rise of the new regime in Damascus, the question of who is the “New Syria” remains open. Syria stands at a critical crossroads: between the possibility of becoming a stable and moderate state with representative institutions and a Western orientation, at least in the economic sphere, or a renewed descent into total instability, takeover by foreign actors, or the de facto establishment of an extremist Islamist regime that threatens minorities and regional stability as a whole.

Ahmad al-Sharaa has succeeded in achieving a significant accomplishment on the international stage, broad legitimacy, the lifting of sanctions, and the opening of doors to aid and investment. However, this legitimacy preceded the construction of governance. State institutions remain weak, centralized, and lacking transparency; the rule of law is fragile; and in certain areas the regime struggles to enforce effective authority and, at times, does not fully control its own security forces. In this reality, economic assistance alone is not a recipe for stability. Genuine reconstruction also requires political accompaniment, institutional guidance, the strengthening of civil society, and education rooted in values of equality and pluralism.

The removal of HTS from terrorist designation lists may have cleared the diplomatic slate, but it did not erase the jihadist ideology that continues to exist among fighters and organizational personnel integrated into the regime and the security forces. Therefore, the lifting of sanctions, an essential step for recovery, must be accompanied by clear conditions, binding standards, constructive intervention and a political–institutional roadmap. Without them, the international community may find itself financing the seeds of the next violent cycle.

Israel, too, must not be tempted by illusions. It should continue to explore arrangements with Syria but remain wary of an “on paper” agreement that is not anchored in real enforcement capacity on the ground.

Al-Sharaa’s declarations that Syria is not interested in confrontation with Israel are insufficient as long as tangible threats persist and the regime struggles to address them.

Israel’s approach must be gradual and integrated: combining freedom of security action with a cautious effort to build cooperation, including the promotion of confidence-building measures. Only through such an approach can it be determined whether the New Syria represents a genuine partner for stability or a reemerging risk cloaked in a diplomatic disguise.

One Response

Dear Dr Zoe,

Thanks for your comprehensive reporting and analysis. As I see the state presently:

1. Syria is an unstable jihaddist proxy state.

2. AlSharra is an islamic jihaddist in disguise.

3. There is no foundational good government.

4. Sharia law indoctrination continues.

5. Death and oppression continue.

6. Violence is part of the state forces terror.

7. Alliances are sought with world despots.

8. Turkey is an evil force seeking power and influence for regional caliphate control.

9. Syria is a growing regional terrorist threat.

10. All jihaddists must be destroyed to bring any sustainable governmental stability.

11. No jihaddis, no innocent dead bodies.

12. Its time to execute Justice against jihaddis.